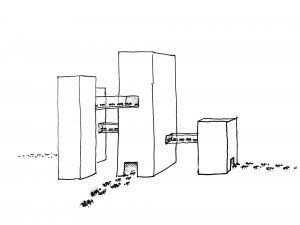

Zachary Tang, a 27-year-old filmmaker, lives in the Bedok section of Singapore, in a building constructed decades ago, before the city became a wealthy financial hub. Back then, rickshaws rattled down streets lined with hawkers, laundry drip-dried on balconies and chaotic canopies of electrical lines clung to the sides of buildings. During this era, to save money, many apartment complexes were built in such a way that their elevators didn’t stop at every floor. Tang’s building was one of them.

“You had to go to the 6th and 11th floor,” Tang says of the apartment complex where he still lives today. “Then you would walk down the common corridor and take the stairs down to your floor.”

This roundabout way of reaching one’s unit led tenants through winding breezeways and stairwells, past open apartment windows and, often, right into direct contact with their neighbors. These chance encounters capitalized on a unique feature of Singaporean housing: its remarkable racial diversity, which is orchestrated by the government as part of Singapore’s Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP).

The EIP was introduced in 1989 to counter the emergence of ethnic enclaves. It does this by placing quotas on how many residents of one racial group can live in a building. The EIP recognizes four categories of racial groups: Chinese, Malay and Indian — the three biggest groups by population — as well as ‘other,’ a catch-all for everyone else.

The quotas apply to every public residential building, and correspond to national proportions so that each apartment complex reflects Singapore’s true ethnic makeup. This degree of micromanagement is only possible due to the fact that four out of five Singaporeans live in Housing Development Board (HDB) flats — public housing built and operated by the central government. Having most citizens in public housing allows the government to exercise a large degree of control over their social dynamics. The EIP is perhaps the most visible sign of this control.

The EIP ensured that Tang’s building was home to a representative cross-section of ethnic groups. Combined with the quirky elevator situation, this meant that Tang interacted frequently with neighbors whose backgrounds were different from his own. Today, the elevators in Tang’s building have been upgraded — now they stop on every floor, reducing the amount of time he spends traversing shared hallways and stairwells.

The EIP is the reason Singapore’s buildings and neighborhoods are integrated in a way that Western cities could hardly imagine. Building by building, block by block, a truly representative mix of ethnicities live side by side. But the EIP sometimes leads to odd outcomes and unintended consequences, byproducts of a highly control-oriented approach to ethnic diversity.

A multi-racial, multi-religious city-state, Singapore has one of the most diverse populations in Asia and is the third most densely populated country in the world. Nearly six million people are packed onto an island just four times the size of Washington, D.C. Yet, it is also renowned for its apparently seamless functionality — social trust is high, corruption is low, and crime and violence are rare. This tranquil, multicultural environment didn’t come about by accident. It is, in part, the product of a strong central government that dictates certain aspects of everyday life — and sees racial harmony between its people as too important to be left to chance.

Racial dynamics have strongly influenced Singapore’s history. Faction between races engendered the country’s independence when it separated from predominantly Muslim Malaysia in 1965. In Singapore’s founding years, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew pulled the nascent city through the tumult of ethnic riots. Lee saw the riots as products of the city’s segregation, and in turn, racial and religious integration as key to Singapore’s peace, prosperity and progress. This ideology was embedded into the nation’s Pledge and written into the Constitution.

As such, institutional measures now regulate ethnic mixing across all aspects of life in Singapore—in residential districts, schools, National Service and electoral constituencies. The EIP is the most all-encompassing of these mandates. Even in the HDB flat that I used to live in, where the elevator stopped at every floor, getting to my unit meant passing six other units with windows that looked out onto the corridor. Through one window I might see a family having dinner. Through another I would spot a young man at his desk synchronizing music. Somedays a neighbor, a middle-aged woman, would be in the common corridor watering her plants. We’d greet each other, wave or quip about how my walking down the corridor was the reason for their dog yelping frantically.

Ng Qin Wei, a 24-year-old dental assistant who lives in the neighborhood of Tai Chee, told me of her neighbors, “We greet each other in the lift and when we pass by. They’ll ask about our work or studies… Most of our neighbors are aunties, uncles, so they’ll talk about their grandchildren. Sometimes they’ll come over and play so we will hang out.”

“We don’t just live with them,” adds Ng. “We study with them — every class has its own quota of ethnic groups as well. We grow up with each other, we think we are just equal.”

Common spaces in the HDB blocks offer additional areas for chance interaction. The most ubiquitous of these is the void deck, the first floor of almost every public housing block, which is a shared space for everyone who lives there. With public benches, tables, small shops, vending machines and even kindergartens and elder care centers, the void deck is a concrete government intervention to foster social interaction.

Mohd Ilyas Amir, a Javanese Singaporean who lives in the Central area of Bukit Merah, has lived in the same block his whole life. “I used to play in the void deck with my Chinese friends, Malay friends, Indian friends,” he told me. Now 22, he still spends plenty of time at the void deck, “for the breeze and to feel the air.” The void deck is also the de-facto space for social events, like Malay weddings and Chinese funerals, which sometimes take place side by side.

But the EIP’s biggest impact might be that by integrating neighborhoods, it also integrates schools. “Once people live together, they’re not just walking the corridors every day,” said Singapore’s Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam in 2015. “Their kids go to the same kindergarten, they go to the same primary school … and they grow up together … Where you live matters… It matters tremendously in the daily influences that shape your life”

According to Leong Chan-Hoong, policy researcher and professor at the National University of Singapore, the EIP has been very successful at integrating the city. One in every three HDB blocks has achieved a balance between Chinese, Malay, Indian and ‘other’ residents, reflecting Singapore’s population. This is an increase from one in every four blocks in 1989, despite more housing blocks being constructed over the years.

According to Leong, this mixing is crucial to maintaining Singapore’s stability. “When you unwelcome people of a different background,” he believes, you end up with social and economic problems. For instance, a neighborhood’s ethnic makeup influences housing prices. In Woodlands, where there is a high proportion of Malay Muslim households, Leong observed housing prices tend to be much lower. “That means you will not have the same capital appreciation in the next 20 years or so, so you wouldn’t want to live there,” he says.

“Without the policy,” says Leong, “it is very likely you will have a sharp differentiation of neighborhoods, and that will not go well with the idea of a harmonious coexistence between people of different backgrounds.”

Harmonious coexistence as engineered by the state has consequences, however. For one, by effectively banning ethnic communities, the EIP makes it pretty much impossible for any minority ethnic group to flex its political muscle. “As a result of the quotas, ethnic minorities are spatially dispersed,” according to a paper presented at the Constitutional Design and Ethnic Conflict Conference at New York University in 2012, which means they are “relegated a minority status in each district and face difficulties raising support for issues particular to their community or ethnicity.”

The EIP also leads to inefficiencies in the island’s scarce housing. A 2017 study by the Association of Muslim Professionals found that apartments reserved for Chinese residents in cheaper estates sat vacant, presumably because wealthier Chinese didn’t want to live there. Likewise, apartments for Muslims in higher-priced areas like Bedok were difficult to fill.

Other logistical snafus arise when mixed-race Singaporeans try to rent or buy an apartment. Does a Chinese-Malay resident count as Chinese or Malay in regards to the quota? Most of the time, whichever part of their hyphenated identity comes first — as it was recorded at birth in the hospital — is their official ethnicity in the eyes of the HDB.

Lee Kuan Yew brushed aside such complications. He argued that, despite small flaws in the EIP, the societal tranquility it gifted Singapore with trumped other concerns. “We had to mix them up,” he is quoted as saying of the city-state’s ethnic groups. “Those who say we should cancel these restrictions… just don’t understand what our fault lines are and what the consequences can be.”

Whether this enforced ethnic mixing — and the general absence of strife — represents true racial harmony, on the other hand, is another question. Dr. Liu Thai Ker, considered the master planner of modern Singapore, has been quoted as saying, “I have built you the kampong. Now show me the kampong spirit.” In Singapore, kampong is the word for a small, local village, the kind that once could be found all over the island. What Dr. Liu meant was, as a bureaucratic tool, the Ethnic Integration Policy can provide the mechanics of racial harmony. Kindling the corresponding mindset, however, is something Singaporeans must do themselves.