As the pace of change in our world accelerates, humanity is confronting unprecedented challenges: the climate crisis, economic inequality, endemic military conflict, the coronavirus pandemic, police brutality and systemic racism. At a deep, primal level, this degree of transformation triggers anxiety both about the future and about who we are. We often wonder, will we even have a future?

But as we approach uncertain futures, there are many paths we can take. Some incite more fear and polarization, while others encourage cooperation, collaboration and solidarity. One makes the “other” a source of that fear and anxiety. A more hopeful approach sees each other as a source of connection and possibility.

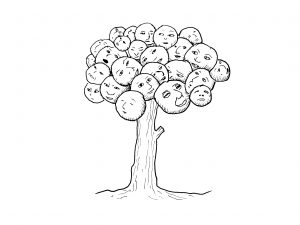

This is the time to discern the difference between them — between actions that can instigate what we call breaking, and those that can lead to what we call bridging. Breaking causes fractures; bridging fosters cohesion. When we break, we propagate a fabricated notion of separateness. When we bridge, we soften our identities. We discover multiple identities.

But bridging is not same-ing. Colorblindness, assimilation and smoothing over difference as though it does not matter bypasses much needed repairs we need to make.

Bridging is about increasing acceptance of diverse peoples, values and beliefs while giving us greater access to different parts of ourselves. Building bridges can help expand our social networks, revitalize our communities and establish a more fair and equitable society. It can help us build a large “we” that does not demand assimilation.

So we have a choice. We can either turn on each other, or toward each other.

We can turn our attention to the version of our current reality that says that our common bond is wearing away. Or, we can pivot toward ever-present examples of hope, and find that solidarity is the modality that enables us to thrive.

We find hope in stories of the Jewish and Arab women in Israel driving hundreds of Bedouin women from their remote villages to polling stations to protect their right to vote. We find it in the youth soccer program in Lewiston, Maine, where Somali refugees play side by side with their American teammates to set an example for the rest of their community. We find it in the NFL’s reversal of its position on players taking a knee during the national anthem, and the league’s eventual support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

We also find hope in the fact that BLM is widely embraced by Americans: two-thirds of U.S. adults support the movement, including majorities of white (60%), Hispanic (77%), and Asian (75%) Americans. The growing diversity within the movement is illustrative and informative.

These examples and statistics signal a sea change. Both individuals and institutions are dislodging entrenched belief systems and rebuking pressure to “stick with the party line.” While there’s still much work to be done, these are important representations of bridging in this historic moment as we work to abolish long-standing oppression.

Stories of bridging not only offer a salve in a fractured world, they provide tangible frameworks and replicable strategies. They teach us that oneness is not sameness, and that we can overcome the false illusion of separateness by honoring our differences to weave toward common purpose with many tributaries. We can transcend the notion that difference divides us, and instead see that it makes us stronger.

This moment finds us at an inflection point. We can choose to continue the well-worn path of exclusion, supremacy and othering, fueled by narratives of fear and threats. Or we can elevate stories and practices of mutuality and interdependence. We can interrogate the stories we have and identify what might be the most productive and life-affirming story we can inhabit. We can co-create stories where we care about each other. We don’t yet know how our story will end, but this is a great place to start.

This essay is adapted from On Bridging by john a. powell and Rachel Heydemann.