Cyprien Mihigo has witnessed firsthand the destructive power of tribalism. Before settling as a refugee in Syracuse, New York, he spent years traversing the Congo, his vast and politically unstable homeland, as an International Red Cross field officer, crossing tribal borders at great personal risk to provide aid to the sick and dying.

After moving to Syracuse in 2001, he watched the local Congolese refugee community grow from four families to hundreds of people — and saw the old tribal rivalries continue to haunt them. The intergroup strife that had plagued the immigrants back at home had followed them, 7,000 miles to their new country and right into the new neighborhoods in which they lived side by side.

“This Atlantic Ocean is so huge that you can travel with the hatred, and after 25 or 26 hours in an airplane, bring it back here — and there is nothing to fight for,” says Mihigo. “Carrying the hatred will kill that person.”

For Mihigo, with his background in humanitarian diplomacy and his own inter-tribal marriage — his wife, a Tutsi, was so vulnerable to tribal violence in the Congo that at one point she went into hiding — the urge to move beyond these conflicts and unite the Congolese community in Syracuse was irresistible. He organized a women’s soccer team. He hosted gatherings with Congolese music, the familiar rhythms transcending tribal boundaries. And then he had an even more ambitious idea: he would put on a play.

“The idea of doing the play was because some tribes would not give other tribes the time to communicate — the opportunity would not happen,” says Mihigo, who projects the energy of a young idealist despite being a father of eight with a sixth grandchild on the way. “But if you have somebody using euphemism, not speaking directly to the person like, let’s talk about this, they can talk about it indirectly while having fun. Instead of talking to that person directly, talk to the audience… At the end, they come together.”

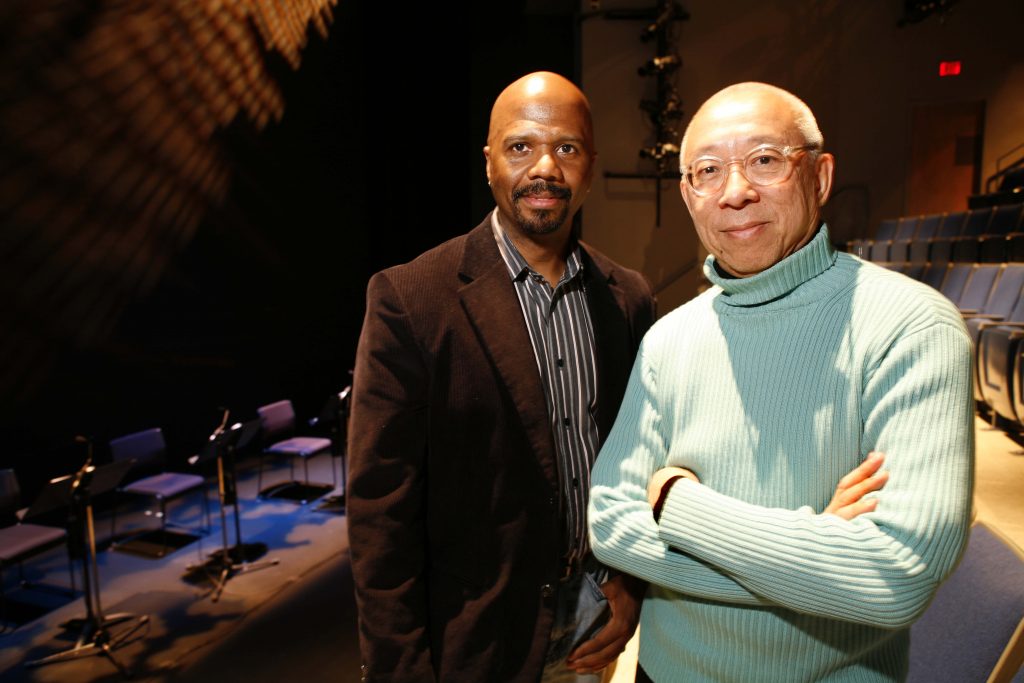

Having never produced a play before, Mihigo literally started knocking on doors at Syracuse University’s theater-in-residence, Syracuse Stage. One of those doors led to associate artistic director Kyle Bass, who introduced Mihigo to internationally renowned director Ping Chong. Their collaboration, Cry for Peace: Voices from the Congo, premiered in Syracuse in 2012, then played in New York City and Washington, D.C. It remains a powerful model for how theater can heal divisions between fragmented communities.

Five performers sit in a semicircle, illuminated by spotlights.They are Congolese Syracusans, Cyprien Mihigo among them. Over the course of 80 minutes, they deliver a narrative that weaves together their life stories, each uniquely harrowing and uplifting, along with a brief history of the Congo and acapella interludes of traditional songs. Though the performers do not move from their seats, the show is mesmerizing, a whirlwind of information and emotion.

It is a formula that Ping Chong has been perfecting for decades. Chong, 73, co-created Cry for Peace under the banner of his Undesirable Elements series, using performers who are, as Chong describes it, “outsiders within their mainstream community” to explore issues of culture and identity. The original 1992 production featured seven bilingual New Yorkers from different countries of origin. As the series grew in popularity, Chong expanded the scope beyond multiculturalism, creating Undesirable Elements productions around people with disabilities, child soldiers and sex abuse survivors. It didn’t take long for Chong to realize that the productions, intended to build connections between people from different cultures, also worked as a kind of therapy for the participants.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

“I realized it was about creating a space for people to address things that they often weren’t able to speak about in the societies that they were in, and then people would just sort of pour their stuff out — stuff they haven’t had an opportunity to vent,” Chong says. “I was quite naive and willing to go places [during the writing process] that were tricky because I didn’t know any better.”

More than 200 ethnic groups co-exist in the Congo, and decades of violence, civil war, Western exploitation and political corruption have turned tribe against tribe, resulting in massive death and human rights violations, and compelling millions of Congolese to seek international asylum. When refugees arrive in Syracuse, says Mihigo, they often carry the conviction that “living in a kind of division or segregation was their right, was normal, and was a way of defending themselves.”

When Bass shared Mihigo’s idea for a play about these refugees, Chong was immediately on board. He knew Cry for Peace would be different from any other play he’d created — for the first time, he would be casting performers from ethnic groups that were in direct conflict.

Chong came to Syracuse, where, along with Bass and his associate director Sara Zatz, they would cast the play, write the script based on the performers’ stories and direct the show for Syracuse Stage. Mihigo was assigned the role of dramaturg and “cultural consultant.” No one was quite sure what to expect.

On the day of his first meeting to gather information, Chong brought five pies for refreshments. The production team had invited Syracuse’s Congolese residents to show up and share their stories. They expected a small handful of participants. Instead, says Bass, “50 people in their absolute finest clothes showed up at Syracuse Stage. It was actually quite beautiful.”

As per the Undesirable Elements format, only five performers were selected for the final cast. Mihigo was among them. “I had to be in it, according to Ping Chong and Kyle Bass, and I had to force myself to be part of it,” says Mihigo, who had hoped to remain behind the scenes. Each member of the cast hailed from a different tribe and had a story they were burning to tell.

Emmanuel Ndeze, 39, fled his village as a young man, relying on strangers for food and shelter. Mona de Vestel, 46, the daughter of a black African mother and a white Belgian father, was born into a family divided by Colonial history, violence and bigotry. Kambala Syaghuswa, 30, was a former child soldier who watched other boys in the Congo “kill each other over an avocado, when there are millions of avocados.” Beatrice Neema shared the nightmarish story of a woman who endured sex slavery and witnessed her family’s murder — she introduced herself by saying, “I am telling this story for someone else because her voice has been silenced by shame.” And finally, there was Mihigo, 48, who had to remove bodies from rivers and negotiate with a gun in his mouth during his time with the Red Cross. His story — of intertribal marriage, of atrocities witnessed, of efforts to create a united Congolese community in the United States — tied the others together.

At their first rehearsal, the cast read the play that Bass, Chong and Zatz adapted from their stories. Bass was struck by the cast’s deep nostalgia and love for the Congo, even as they shared their war stories. The first time they practiced with a projection screen, they were so excited to see a slide of the Congo that many of them pulled out their phones and took pictures of the giant map. “It was one of the most stunning things I’ve ever seen,” said Bass.

Within Syracuse’s Congolese community, however, some were skeptical. They told Mihigo that the cast’s life stories would be exploited, or that the play would dredge up bad memories “for no reason.” But Mihigo believed in the play, and its capacity to ease “the little hatreds on the heart,” as Mihigo said to Bass in his pitch, that tribal conflict had planted.

“The tribal element is very real,” says de Vestel, who was volunteering as a translator for Congolese refugees when she joined the cast. The Belgian-born daughter of a white father and a black African mother, de Vestel lived in the Congo before moving to the United States in 1979 with her mother and stepfather at the age of 13. Tribal violence had touched her extended African family, but Cry for Peace was the first time she had seen different tribes grappling with each other’s experiences together. “I was the only one that was biracial, but the others were from different ethnic groups and it was really super intense for me to even witness that,” she recalls.

Once performances began, the power of Cry for Peace was immediately apparent.

“We got amazing responses from the audience,” says de Vestel. “I think it really resonated for people to see such a seemingly different group of people — people that should not like each other, with a complicated history — tell the story and connect on a human level.”

In the Undesirable Elements anthology published in 2012 for the 20-year anniversary of the project, Zatz writes that the plays are intended to have “three levels of impact.” First, they create community between people who might not otherwise know or speak to each other. Second, the performers open up to the audience during the performance, creating a kind of community within the theater. Third, everyone — participants and audience alike — returns home, where they can use that experience to impact their own communities. During the Cry for Peace production, de Vestel watched this process unfold.

“I know that [Cry for Peace] brought people together because I witnessed it,” she says. “We were very connected, at a very deep level… When your perspective shifts, I think that’s a wealth that you bring back to your community, to your life. And I like to believe that it trickles to other people, too.”

“Did it revolutionize the community? I don’t know,” she adds. “But I think it was a revolution for us.”

That was certainly true for one cast member. Beatrice Neema had recently moved from a refugee camp and spoke almost no English when she joined the cast. Nevertheless, she delivered the most devastating story in the production, of a woman raped into unconsciousness by soldiers while listening to her husband and child being killed in the next room. She said it wasn’t her own story, but rather the story of a woman she knew. “I have told this story for someone else,” Neema reminded the audience. “Syracuse, New York is now her home. Perhaps someday she will be able to tell her own story.”

What the audience didn’t know is that the woman “silenced by shame” was actually Neema herself — afraid of being shunned by her new community, and embarrassed by her broken English. But over the course of productions in New York and Washington, D.C., something shifted.

“When we first did the show, Beatrice said, I want to say it’s somebody else’s story that I’m telling, and I want to speak French,” recalls Chong. “And I said, fine. We had a translator on stage and she told her story. And then we did the show again and she said, I want to tell the story in English, but still say it’s somebody else’s story. By the time we had done the show a couple more times, she wanted to say it was her story. “

For Bass, seeing Neema’s story change from the third person to the first person represented the ultimate reconciliation, “her own interior reconciliation with herself and her own story.” To some extent, he says, he watched all of the cast members have that same experience. Mihigo has seen similar changes throughout Syracuse’s Congolese community. “People are not afraid of each other anymore,” he says, though some longstanding cultural and language rifts remain.

Regretfully, due to an administrative change at Syracuse University, Ping Chong and Company lost their funding before Cry for Peace could be performed in additional cities. Still, almost a decade after he first pitched his idea, Mihigo has hopes of producing a new play for a cast of Congolese refugees. He sees the divisions in his adopted nation, the heated political debates over racism and immigration, as an opportunity for his community to speak a truth that the rest of the country needs to hear.

“I’m a very small person. Nobody knows me much, but the only way I can try to get the attention of people is by being in a play and to pass not only my message, but the message of the community, the message of people of color, the message of immigrants and refugees,” says Mihigo. “Our point of view is important. Our word is important.”

After working with Ping Chong and Company on Cry for Peace, Mihigo knows that through theater, even the most divided people can learn to listen to one another. “We could make a play that would play in any country, and people would applaud it,” he says.