In March 2004, the headmaster of the school where Carol Ramolotsana worked called her into his office and handed the young religion teacher an envelope. It carried the stamp of the Ministry of Education, which could mean only one thing: a transfer. Carol opened the envelope and read the name of her destination: Lentsweletau. “Lion Hill.” She began to cry.

At home, she looked up Botswana in an atlas, her finger searching the map until it settled on a small point on the edge of the Kalahari Desert. Lion Hill, population 4,000, was home to the Bakwena tribe, who worship crocodiles.

Carol, a sophisticated city girl, had known this day would come. After all, this was Botswana, where teachers, doctors, nurses, administrators and other civil servants are shipped off against their will to remote regions of the country, expected to sacrifice their own freedoms for the collective good. It’s an extreme model of governance. It also works extraordinarily well.

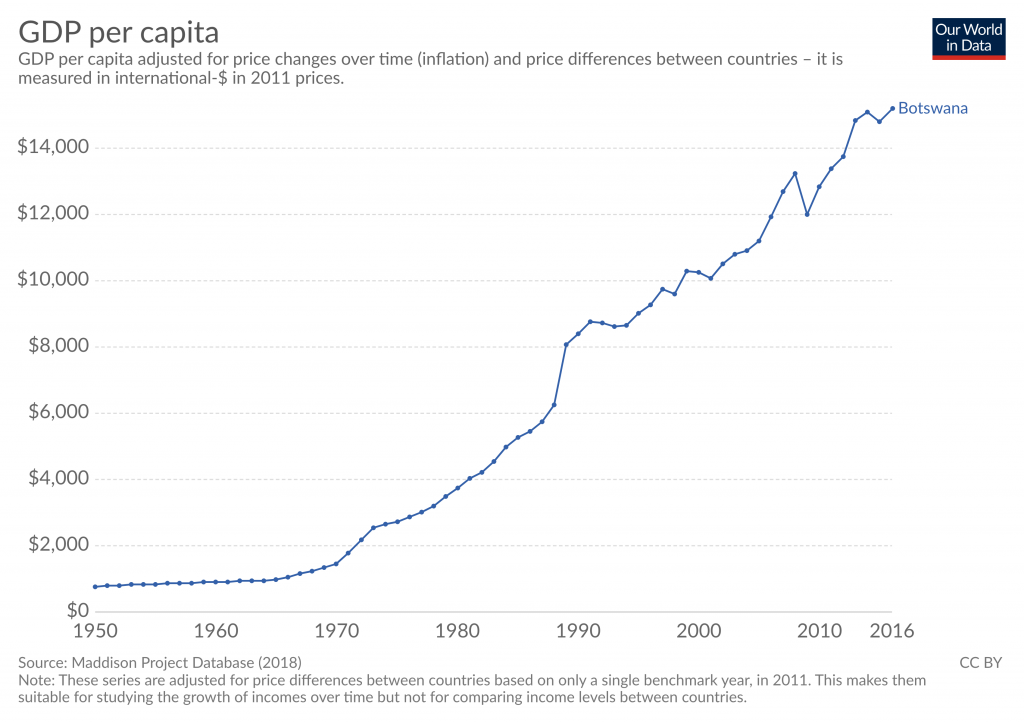

In the 1960s, as dozens of countries in Africa began to decolonize, their leaders promised prosperity and development. Instead, oftentimes, violence broke out, economies withered and infrastructure crumbled. But one country kept its promise: Botswana. In the three decades after independence in 1966, Botswana had one of the fastest growing economies in the world. It went from having 12 kilometers of paved roads to over 18,000. In 1966, it had 22 college graduates — now, it boasts a highly educated populace, many of whom studied in South Africa, the U.S., Great Britain or Sweden. After a few years, these graduates returned and built ministries and hospitals, universities and airports. They ran power lines and water pipes through the savannah.

Today, education in Botswana is largely free, from kindergarten to university, and Botswans pay nothing for visits to the doctor, and just as little for seeds, fertilizers and harvest workers. According to Transparency International, Botswana is the least corrupt country in Africa, and less corrupt than many European countries, too, including Italy, Spain and Malta.

When Botswana’s colonizers drew its new borders, they tore apart tribes who wanted to be together and locked together others who didn’t. This sort of reckless divvying up had led to chaos in countries like Nigeria, the Congo, Mali and Rwanda. But in Botswana, that didn’t happen. Instead, Botswana’s tribes drew closer as one nation.

When I traveled through the country in 2018 and spoke to dozens of Botswans about their identity, not a single one mentioned their tribe. They said first and foremost: “I am a Botswanan.” This loss of tribal identity runs counter to what many other societies now recognize as an important element of diversity: namely, people’s right to hang on to who they are, even as they come together as a unified group.

In this way, Botswanans have made a monumental sacrifice for the tranquility of their nation — they have deprioritized their deeply held tribal identities for the sake of societal stability, and in the process, formed a unified state out of a multiethnic, multilingual, partially hostile tribal society. This sacrifice can’t be discounted, and yet it has worked. Today, thanks to these sacrifices, Botswana is perhaps the most successful example of nation-building in history.

The reason this happened is the same reason that Carol Ramolotsana, a happy 29-year-old who loved going to the movies, grabbing Chinese food with friends and frequenting O’Hagans Pub, found herself, a few days after receiving the notice from the headmaster, watching as her couch, her refrigerator, her bed, her whole life, disappeared in a moving truck that then rumbled off towards the Kalahari.

A few days later, Carol was following the same route in her Honda Civic. Soon, the glittering towers of Gaborone disappeared in the rearview mirror. The road narrowed, the landscape widened. When she arrived in Lentsweletau, the first thing she saw was a crumbling building and a half-finished gas station. No cinema. No pub. No Chinese restaurant. The school consisted of a few dozen shacks scattered across the red earth.

In her small brick house, Carol sat on her bed and cried. It was days before she stepped into her high heels, hung a purse in the crook of her arm and went to class. Her new colleagues laughed at her outfit.

“The fine lady,” said one.

“You won’t wear the shoes for long,” said another.

Carol spent the lunch breaks alone in her house. At night, she drove to the village bar, ignoring the looks. She ordered beer at the counter and drank it outside, alone in her car. Five, sometimes six cans in the evening. Then she drove home and slept.

When Carol was transferred to Lentsweletau, she was consumed with resentment. Why does the government have to bring teachers from the city to the country? Why can’t everyone work where they come from?

I put these questions to Simon Coles, deputy minister at the Botswana Ministry of Education. He sat behind a wooden desk piled with letters, printed emails and transcripts of phone calls eight inches high.

“All complaints from dissatisfied teachers,” said Coles, gesturing at the piles. “Most of them are thrown out.”

Botswana’s civil servants — 120,000 people, around ten percent of the working population — often complain about the fact that they could be transferred to another part of the country at any time. If a rural clinic needs a new nurse, if a distant district office requires a driver, if a far-flung town hall needs a secretary, the government ships someone out. Many try to get out of it. Few are successful.

“We owe our national unity to the transfers of officials,” says Ponatshego Kedikilwe, Botswana’s former vice president. He explains that Seretse Khama, the first president of the independent Botswana, observed how tribalism was tearing apart one African society after another. Botswana had tribes too, each with its own territory and chief, and usually represented by an animal. There were the Kalanga in the north, the good-natured elephants. There were the Batswena, the crocodiles, a warrior people. And there was Khama’s own tribe, the Bangwato, the antelopes, which, even then, were seen as the elites.

Khama knew that these tribal identities would have to give way to a national, shared identity — a painful sacrifice to ask one’s people to make, but one that the government felt was the only way to avoid the fates of other African countries that had struggled to unify following independence. At the same time, the government had to ensure that rural people could go to school or see a doctor. So it began shipping out its civil servants, who often belonged to a different tribe than the place they were sent. It quickly became clear that these transfers were having an interesting side effect.

The officials made friends with the people whom they were sent to serve. Some fell in love, got married and had children — children with parents who belonged to different tribes and sometimes even spoke different languages.

All over the country, in thousands of one-to-one contacts, prejudices fell and new bonds were formed. Exposure, says Kedikilwe — that was the key. Every citizen must be exposed to his fellow citizens, regardless of tribe.

After arriving at Lentsweletau, Carol Ramolotsana only left her home to teach and drink. She resisted exposure. Until one Saturday in the spring, five months after she had arrived.

That morning she had driven an hour southwest of Lentsweletau for a change of scenery. She sat on a plastic chair in front of the “Big 6 Bar” and drank a beer. When it was almost empty, a man got up and got her a new one. He was tall and handsome, with strong shoulders and a broad smile. He was a soldier, he said. His name was Thabo.

“Where are you from?” he asked. Lentsweletau, Carol said.

“Really?” he replied. “That’s my home village.”

He visited her a week later. Another time, he brought friends and took her to a wedding party. He had bought her three skirts, and she felt like her old self, when she would dress up and hit the town in Gaborone.

Thanks to Thabo, Carol soon felt more at home on Lentsweletau. She attended the festival of the village choir, where goats were slaughtered. She became a juror in the local beauty pageant. She danced at weddings and cried at funerals. “At first I was so angry with my employer that I transferred this anger, this hatred, to everything that was near me, including the village and the people,” she says. “Thabo took my hatred away and suddenly everything appeared in a different light.”

It takes surprisingly little contact to break down even the most persistent divisions. In one of the last great battles of World War II, the German and American armies battled for a bridgehead. It was defended by the American Company K, among others. Many of Company K’s soldiers had already been killed, and others were injured. If reinforcements didn’t come soon, the Germans would overrun them.

Then, on the afternoon of March 13, 1945, they heard gunfire from the forest below their position. “The men feared the worst,” writes American author David Colley in his account of the scene. “Then they saw a jagged line of soldiers emerge from the forest. They were relieved to see that the men were wearing olive uniforms and the pot-shaped helmets of the U.S. Army. But as they got closer, the GIs of K Company saw that the faces of these men were brown… Their relief turned into shock. It was Black Americans who came to their aid.”

Like all of American society back then, the army was segregated by race. But in the closing stages of World War II, for the first time since its formation, the U.S. Army broke its doctrine of segregation. One of these Black soldiers, J. Cameron Wade, later said: “We ate together, slept together, fought together. There were no incidents, the army couldn’t believe it.” They held the bank. Then they marched further east, towards victory.

Afterward, to find out how this inadvertent social experiment had affected those involved, the Army sent researchers to question the soldiers. 77 percent of whites who fought with Blacks said they liked and respected Blacks better now. When asked how the Black soldiers fought, 84 percent of the whites questioned answered “very good,” and the remaining 16 percent with “good.” A Nevada company commander said, “You’d think it couldn’t work. But it did.” A sergeant from South Carolina: “When I saw them fighting, I changed my mind.” A platoon leader from Texas: “We all expected difficulties — there weren’t any.”

After the war, Gordon Allport, one of the most brilliant social psychologists of the 20th century, found himself poring over the Army’s research in his office at Harvard University. As it turned out, in the last months of the war, the researchers had questioned not only those soldiers who had fought with Black comrades, but 1,700 U.S. soldiers, asking them all the same question: How would you feel if your unit included Black platoons?

Because the army, with its divisions, regiments, companies and platoons, is so confusing, a somewhat simpler comparison might help: Let us imagine four groups of white soldiers. Group one consists of the men who fought alongside their Black comrades at the front lines. Group two consists of soldiers across the river who watched the fight through binoculars. Group three is made up of soldiers who only heard the battle through their radios. And group four consists of soldiers who weren’t anywhere near the fight — they were back in the U.S.

Now, imagine that all four of these groups were asked the same question: ” How would you feel about serving in a unit with Black soldiers?”

Of the soldiers in the fourth group, who were back in the U.S. thousands of miles away, 62 percent said they strongly disliked this idea.

Soldiers who heard the battle through their radios, however, had a different reaction: only 24 percent of them disliked the idea of fighting alongside Black soldiers.

Of the soldiers in group two, who watched the battle from the other side of the river, only 20 percent disliked the idea.

And as for group one? The soldiers who had actually been there in the trenches, fighting alongside Black Americans, had almost no problem with it anymore — only seven percent of them didn’t want to serve alongside Black soldiers.

The more contact, the less prejudice. And then Allport found something even more fascinating: a second row of data in the same document.

The researchers had also asked the soldiers about another group of people: the Germans. Of the American soldiers in group four — the ones who have never been to Germany — 74 percent had a negative view of Germans.

Of the soldiers who were in Germany but had no contact with the civilian population, only 51 percent had a negative view. Of those who had had brief contact with German civilians, only 43 percent felt negatively about them. Among soldiers who had had closer contact, that number fell further, to 24 percent.

In other words, the soldiers who were physically closest to the population of the country they were fighting had the most positive attitude toward that very population.

Based on this and other research he conducted, Allport formulated the now well-known “contact theory,” which posits that contact between enemies reduces prejudices and leads to more peaceful coexistence. However, warns Allport, there is a type of contact for which this does not reduce prejudices, but actually reinforces them. Namely, when the contact is so superficial that it arouses a prejudice but cannot attack it.

We can see where a lack of contact can lead. As a reporter, I’ve visited McConnellsburg, Pennsylvania. It has a thousand residents, two traffic lights, 11 churches and a well-frequented gun shop. Eighty-four percent of its residents voted for Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

The people of McConnellsburg told me about the threats to America as they see them: illegal immigrants, liberal city dwellers, Blacks. Yet 97 percent of McConnellsburg’s population is white. City dwellers rarely go there. And there are hardly any illegal immigrants. The residents are afraid of people they don’t know. They’ve created monsters in their heads.

I’ve also met people in New York who refer to Trump supporters as fascists, racists or Nazis. When I ask how many Trump voters they know personally, many tell me they’ve never met one.

Carol once saw the people of Lion’s Hill as similarly separate from her. Now, she feels so connected to them that she would like to remain there forever. On the edge of the village is a large field where an old woman grew watermelons. Carol, who loves watermelons, would visit this field so often that the woman began calling her “my daughter,” a title in Setswana, Botswana’s national language. One day the woman asked if Carol liked a piece of the land. Carol said yes, and the woman gave it to her. Carol started building a house on it. It wasn’t even finished when a letter arrived from the Ministry. Carol was to be transferred again. Her next station would be 200 kilometers north. She could move into the house here later, she told the old woman — at the latest, when she retires. As it turned out, Carol had decided she would like to spend her golden years in Lion’s Hill, and be buried there, too.

In his book Sapiens, Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari tells the story of a group of Homo Sapiens who journeyed from their African homeland towards the Middle East 100,000 years ago. There, they met another species, the Neanderthals. A battle ensued and the Sapiens were crushed. But 30,000 years later, the Homo Sapiens returned a second time. This time they won, and went on to conquer the rest of the world.

What happened between those first and second encounters? According to Harari’s thesis, during that time, Homo Sapiens acquired a skill that no other species had mastered — namely, the ability to speak about things that could not be seen, touched, or smelled. Many species can express basic thoughts: Be careful! A lion! But Homo Sapiens learned to verbalize concepts like: The lion is the guardian spirit of our tribe.

In other words, they invented fiction, which Harari believes is the most important innovation in the history of our species. Because once the Homo Sapiens began to tell stories, they were able to form societies. Myths and legends were spun. God was created. Suddenly people no longer had to know each other personally to stick together. They felt they belonged to one another because they believed in the same stories. “You cannot convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him that, after he dies, in monkey heaven he will get an infinite number of bananas,” writes Harari. “Fiction has not only enabled us to imagine things. It enabled us to do that together.”

Today, human life is dominated by groups that are held together by fictions. Hundreds of millions of people believe in the story of Jesus — they live on different continents, yet form a community. A piece of paper, printed with the right ink and symbols, becomes a thing of great value — about seven billion people believe this story today. And then there are the stories of nations. What is Germany? What is France? What is the United States? Nations are no different from God, money and the law: they exist only in our collective imagination.

But after World War II, globalization began to shoot people around the globe en masse, physically in planes and high-speed trains, virtually through television and the Internet. Suddenly, millions looked beyond their national stories and began to feel less connected to them.

This has caused something of a crisis. Too many people’s group identities have outgrown the national framework, yet we continue to make politics within it. Some Western societies are starting to resemble African states in the 1960s: warring tribes locked in with one another, confined by borders but not beliefs.

Botswana shows us a way forward. The government formed a nation out of a tribal society by weakening the old group identities through thousands of one-on-one encounters. It built a new, national group identity by telling its citizens a new story — a fiction so convincing that many began to believe it.

Contact was their most important tool.

A version of story originally appeared in the book “180 Grad: Geschichten gegen den Hass” (180 Degrees: Stories Against Hate) by Bastian Berbner. Berbner is the host of the podcast 180 Grad: Geschichten gegen den Hass. Both feature stories of overcoming hate and division.

A version of story originally appeared in the book “180 Grad: Geschichten gegen den Hass” (180 Degrees: Stories Against Hate) by Bastian Berbner. Berbner is the host of the podcast 180 Grad: Geschichten gegen den Hass. Both feature stories of overcoming hate and division.