This story was contributed by our partners at Next City.

Marilynn Winn, who was born and raised in Atlanta, got to know the Atlanta City Detention Center at an early age. She was incarcerated at the facility when it was still a small jail. As she spent ensuing years in and out of prison, the jail grew in both size and population.

“I went in and out of the system for a little over 40 years of my life,” she says. She came to understand how the jail — which houses people detained for matters like traffic violations, failures to pay a ticket, disorderly conduct, sex work and shoplifting — could “lead to a life sentence.” And so she set out to close it.

Winn is the co-founder and executive director of Women on the Rise, a grassroots organization led by formerly incarcerated women of color that has worked six years to shutter the jail. A major victory arrived in 2019, when Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms sponsored legislation and signed into law a bill to form the Task Force to Reimagine the Atlanta City Detention Center. The goal of the task force, which Winn joined as co-chair, was to provide recommendations to transform the jail into a Center for Equity alongside policy proposals to decrease criminalization and increase public safety.

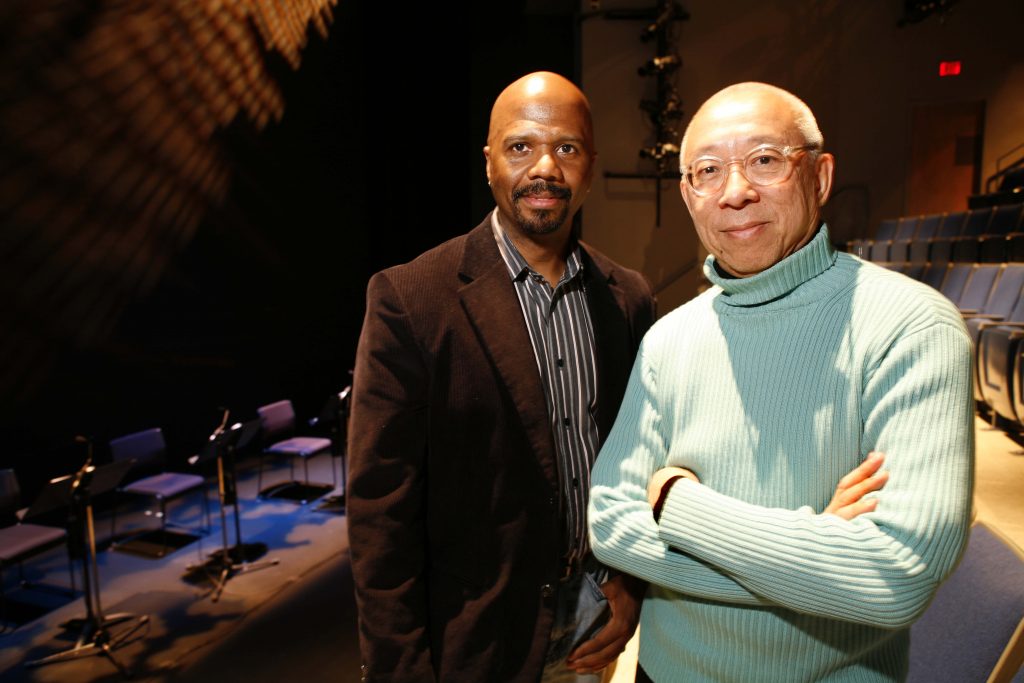

Winn didn’t join a task force in which everyone was on the same page. Alongside community organizers there were government officials that included Atlanta’s chief judge, the chief of police and chief of Atlanta’s Department of Corrections, Patrick Labat.

Labat oversaw the Atlanta City Detention Center. “I am a firm believer that Atlanta, a city this size, needs a place for detention,” he tells Next City.

“Chief Labat and I did not see eye to eye, because I kept saying I want to close your jail and he kept saying you’re not going to close my jail,” Winn recalls. “He and I went back and forth a lot.”

Despite opposing viewpoints, Winn and Labat stayed on as members of the task force during a one-year collaborative reimagining and engagement meant to transform a symbolic piece of city infrastructure. Winn is still an abolitionist organizer and Labat remains in law enforcement. But over the course of the year, they worked together and with broader communities — including those formerly incarcerated at the jail, people who work at the jail and survivors of violence — to reimagine the future of the detention center. The results are four different proposals to transform the jail into a holistic community hub.

To those who believe it’s impossible to close a city jail, “I’m a person that does not believe in the impossible,” Winn states. But she knew from the get-go that engagement around it would be challenging.

Winn led the launch of the campaign to close Atlanta’s jail two years ago. The ambitious proposal was bolstered by years of advocacy that pushed Mayor Bottoms’ administration to adopt new policies and programs to decriminalize low-level offenses, expand a pre-arrest diversion initiative, eliminate municipal cash bail and end a long-term contract with ICE. Winn calls this work “starving the beast,” meaning it all reduced the population of the jail.

The campaign met with Mayor Bottoms last spring to discuss what they’d like to happen with the jail and demand a community-led design process. Later that year the mayor launched the task force. Women on the Rise and the Racial Justice Action Center hired Oakland-based firm Designing Justice + Designing Spaces (DJDS) to lead designing of the architectural structure of the detention center.

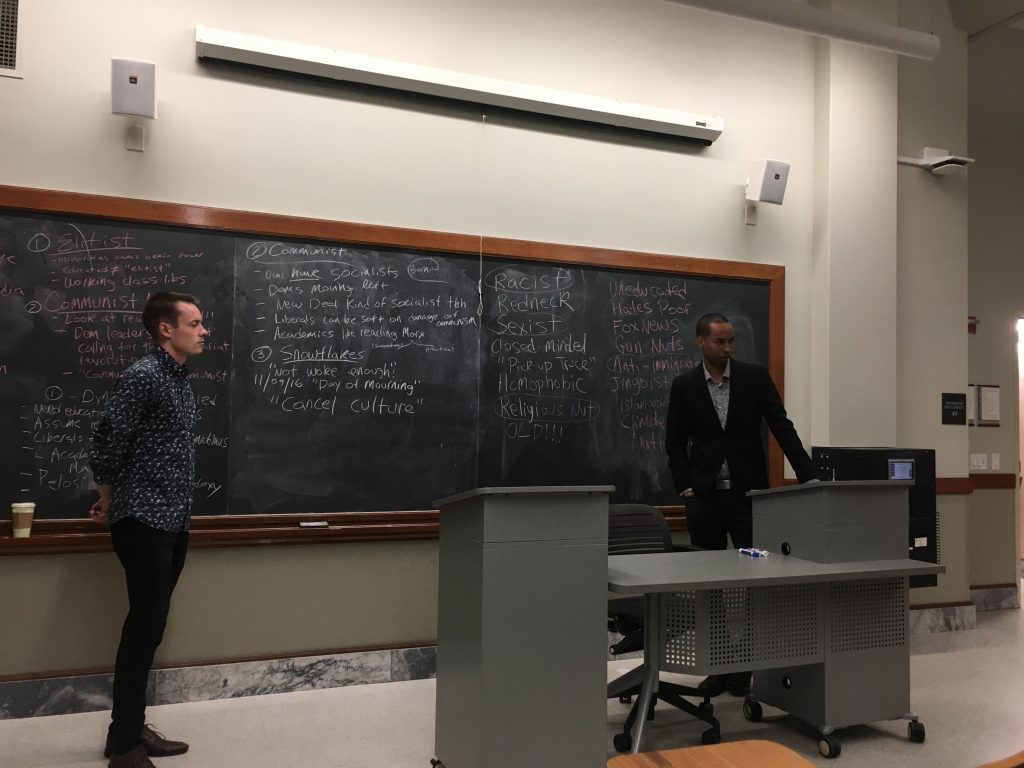

The design process got off to a tense start. Hundreds of people alongside the full task force attended the first city-wide meeting about the project, where community activists expressed exhaustion, law enforcement stated their opposition and correctional officers feared losing their jobs.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

“The campaign had been going on for six years and organizers were already at odds with the police chief,” remembers Shelley Davis Roberts, architectural associate with DJDS. “The community really didn’t believe the city had any intention of closing the jail.”

It would be a monumental task for the firm, which specializes in design to end mass incarceration: They would have to create space for productive dialogue, encourage buy-in from the community, then harness that energy to re-imagine a hulking, 471,000-square-foot carceral facility.

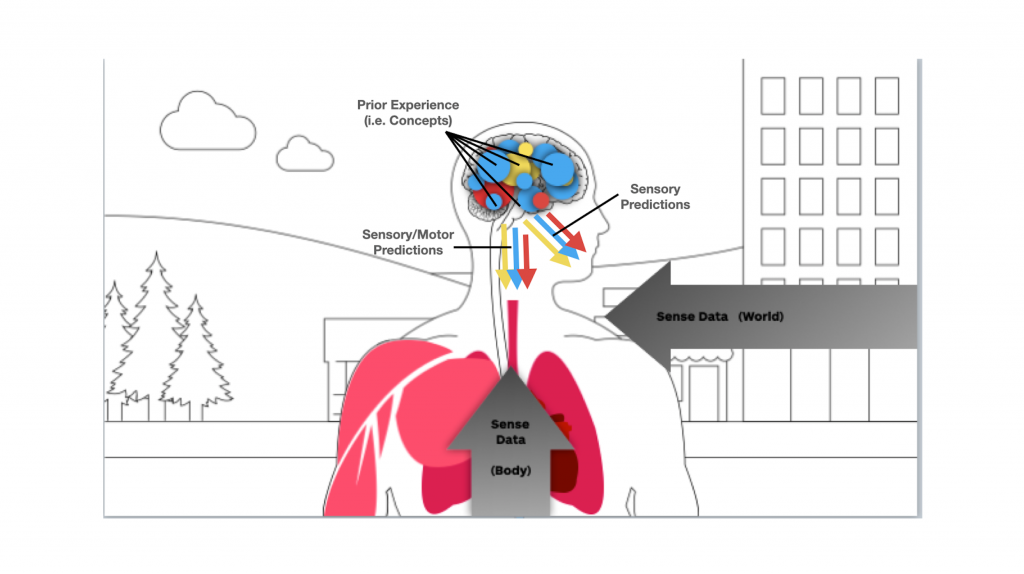

“We went in wanting to shift the thinking around this, change the energy and gain the trust of the community by really demonstrating, through our process, that we care what the community thinks and we’re looking to them as the experts,” explains Davis Roberts.

The community had plenty of insight, as well as experience navigating criminal justice conversations between community organizers and law enforcement.

Community organizers advocating for closure of the Atlanta jail had already spearheaded a design team advocating for what would become the Atlanta/Fulton County Pre-Arrest Diversion Initiative. “Even though it seems painful to bring people from so many perspectives together, it’s like the only thing that gets us to the final agreement,” says Xochitl Bervera, director of the Racial Justice Action Center, an organization engaged in both processes. “If you don’t have the head of the Department of Corrections and police alongside the homeless person who has just been arrested, or the trans woman who has cycled in and out of that jail, you’re not gonna get to where you need to go.”

That process also emphasized alternatives to the policing and incarceration cycle, particularly for people experiencing homelessness, mental illness and extreme poverty. The organizers presented data-driven evaluations from other cities with diversion programs that reduced recidivism and invited law enforcement officials from those cities to talk with Atlanta officials. “It was peer to peer,” according to Che Johnson-Long, a co-coordinator of the pre-arrest diversion design team who also facilitated engagement for the ACDC design process. “We were showing what worked to service providers, law enforcement and community members.”

That design team served as the model for the Reimagining ACDC process, only this time city leadership was more involved and partnered with community organizations and DJDS to facilitate community engagement and use the feedback to design alternatives for the jail.

From the get-go DJDS got creative on engagement. For the first citywide meeting the firm distributed its “Peace and Justice Cards” in which the participants are asked to pick a card that makes them feel peaceful. “Just asking that question causes a shift,” explains Davis Roberts. “We’re engaging people visually with images, we’re giving them a choice.”

The next 12 months included small focus groups as well as larger community gatherings that engaged a total of around 600 people. Groups included formerly incarcerated people, immigrant communities, homeless communities, survivors of violence, harm reduction experts, justice experts, homelessness experts, mental health experts, neighborhood planning units, youth, the LGBTQ community and business owners surrounding the jail.

With each group, the vision for the Equity Center richened. People receiving victims’ services, for example, spoke about traveling long distances across the city to access various benefits. It was suggested the Center for Equity could serve as a “one-stop-shop” for victim services. Engaging surrounding businesses helped participants re-imagine not only the jail, but the entire district as a potential engine for new economic opportunities.

Not everyone was engaged, Johnson-Long admits. “The workers inside the jail did not receive good communication about how the jail was closing,” she notes. “These employees are mostly Black and mostly live in South Atlanta, and we wanted to make sure they also got a say in how the building got redesigned. Unfortunately we didn’t get to do that and it caused a lot of tension.” Johnson-Long says there should have been better frameworks to engage their concerns, like loss of jobs and pensions, and ways to envision new job paths within the Center for Equity.

At larger community meetings, which were open to the public, DJDS used games, like “Seat at the Table,” which presented participants with a 3D model of the city and menu cards, which they used to devise a menu of uses for the buildings.

The “Space Planning and Finance” game was designed to give participants a basic understanding of how spaces in a building are planned and how a project like this would be paid for. “A lot of time there’s a disconnect between what people want to have happen and how you actually fund it,” explains Davis Roberts. “But there’s creative ways to program a building and combine funding sources … it sounds complex, but once you get people playing it can be relatable and fun.”

“For abolitionists and people on the ground who have been fighting, we’ve all been focused for a long time on what is wrong with the system,” says Bervera. “Sometimes our visioning muscles are a bit weaker. It was awesome to dream — even to dream inside the realities of money — and envision something different than what Atlanta has ever seen.”

Johnson-Long found the design games presented by DJDS could take the focus off political tension and instead allow activists, politicians and law enforcement alike to focus on design-based solutions. “We had the chief advisor to the mayor, police chief [Ericka] Shields, district attorney Paul Howard playing these design games and they’re laughing and sitting with community members,” she recalls. “There’s a life that comes to people when you take them out of their heads and have them create an alternative.”

Labat — recently elected as Fulton County Sheriff — stresses the process didn’t push him to radically change his mind about the criminal justice system. “I’m law enforcement through and through,” he states. Still, he says, “the community broke through on understanding how we were going to communicate, that’s the biggest takeaway from me.” He will take the lessons into his new role. “We have a new responsibility, given all the civil unrest and the conversations communities want to have,” he says. “We have an obligation as law enforcement not just to sit at the table, but to have meaningful conversations about putting our community first.”

As Labat takes on his new role, Winn will continue her own as an abolitionist: “I’ll be back and forth at it again [with Labat] as he just won the election to be sheriff of Fulton County Jail, which is overcrowded and some of it needs to be closed up.”

Other divisions remain in place. Bervera points out the mayor’s administration has since cut off community dialogue in regards to the four proposals released by DJDS. “The task force has been dissolved, the planning team has been dissolved, the mayor’s office is not forthcoming,” she notes. “It’s clear that they have eliminated any real community power in this phase.”

“Community and government partnerships mean shared power — you need structures and systems, not just collecting input from the community and creating a glossy report,” Bervera continues. She believes the engagement around the task force — a process she calls “exhilarating, frustrating, inspiring and exhausting” — was a good first step.

Until the city closes the facility and makes a decision around the ACDC proposals, “community organizers and leaders will keep up the fight to end criminalization in their communities and transform the jail into a center for wellness, equity and freedom,” Bervera states. “We believe we have not won the campaign,” Winn says, “unless we put something in its place.”

A version of story originally appeared in the book “

A version of story originally appeared in the book “