Like a lot of folks, I occasionally hear people espouse values and beliefs different and often counter to my own. When I was young, I didn’t understand this. Many of these beliefs and positions seemed irrational to me. How could people believe such crazy things? But as I read, traveled and met more people, I learned that values and convictions that might seem strange to me often serve a purpose for others.

Sometimes that purpose is simply the sharing of these values and beliefs with others who feel the same way. Shared beliefs can foster a sense of community, or provide meaning in people’s lives. It seems that we as humans have evolved to need something that provides unity and cohesion. Sometimes that might be liking the same songs or movies. Or, if that means believing in statues that cry or space aliens, well, okay, maybe no harm done.

I have come to sense that I, too, might harbor some odd beliefs — and, like others, I come up with convoluted rationalizations for them. I have a set of values that, to me, should be seen as self evident and should therefore be adopted by everyone. But if we’re going to find common ground and live together, we need to at least attempt to understand the mindsets of the people who think differently from us.

Some years ago the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt proposed in his book The Righteous Mind that there are six basic moral values, and how important each value is to us as individuals determines our behavior. I am not interested in debating how innate or universal these values are, or if there are more or less than six, but I do find them a useful tool for understanding those with views different from my own. These tools help prevent me from feeling superior. They allow me to imagine what someone else might be thinking and why they believe what they believe — because we actually share many of the same values.

Here are the values (and their opposites):

1. Care/Harm. We are all one family and should have compassion for everyone else, as much as we can. Suffering should be eliminated if it can be.

2. Fairness/Cheating. A society should strive to be fair. Justice should be equal for all. Cooperation is better than cruelty. The flip side is that cheaters and free riders should be scorned or punished.

3. Loyalty/Betrayal. Loyalty to one’s family, community, team, business and nation is essential. It is the force that holds things together.

4. Authority/Subversion. One must abide by the law, whether one agrees with it or not. Our collective agreement to obey social and legal institutions is what makes us function as a society.

5. Sanctity/Degradation. Purity, temperance, restraint and moderation stabilize our world. Certain behaviors are immoral and must be shunned.

6. Liberty/Oppression. People should be allowed to be free in their speech, thoughts and behaviors as long as they aren’t hurting others.

I find that, to some extent, I can see the worth in every one of these six values. None of them seems completely wrong. That said, clearly I have my personal leanings. I value some more than others. That’s exactly the point. The idea is that folks tend to prioritize some of these values, and which ones we prioritize determines our politics, how we behave and how we think of others. I do this, you do this, we all do this.

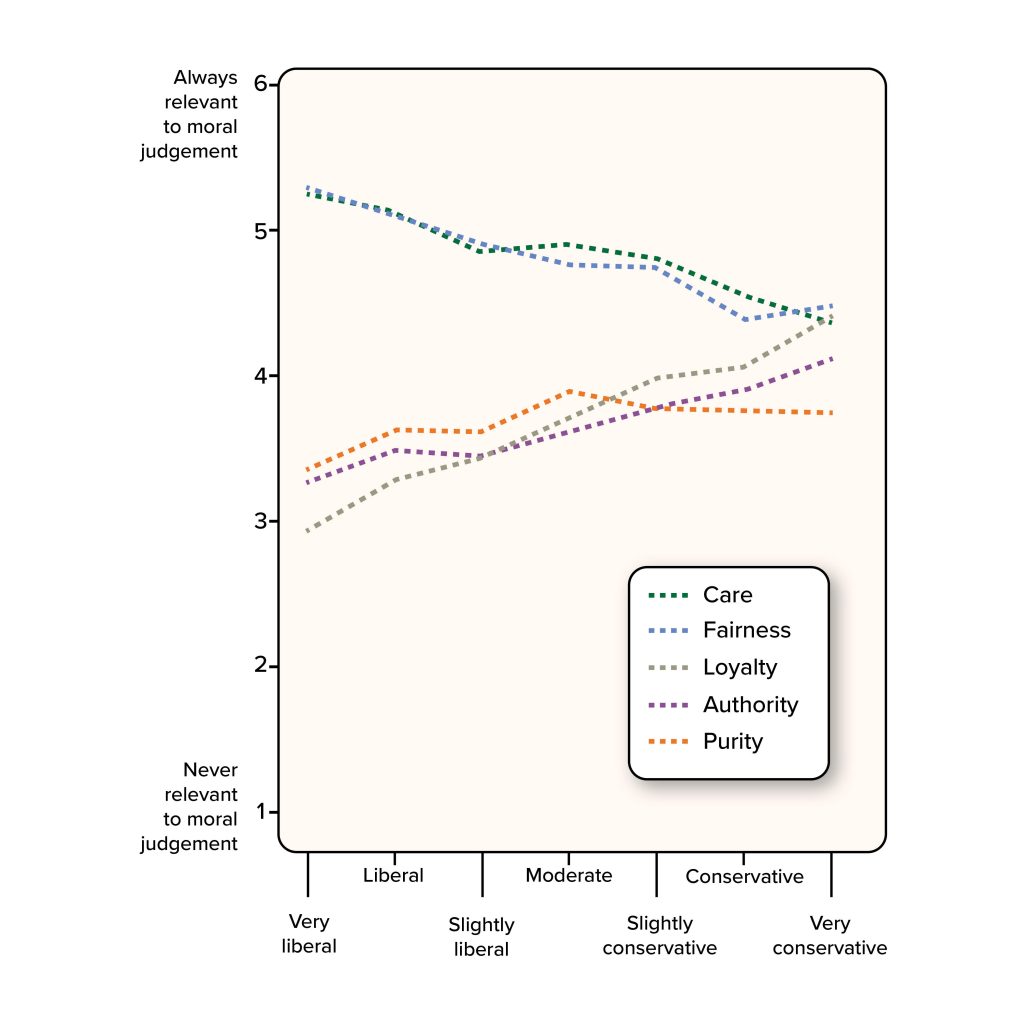

The values we prioritize, says Haidt, determine where along the political spectrum we fall. Whereas liberals tend to emphasize care and fairness, conservatives are somewhat more apt to value loyalty, purity and authority (though, as Haidt points out, neither group discounts care and fairness all that much — it’s on loyalty, purity and authority where liberals and conservatives really diverge.)

So, for example, as someone who places a high value on care and fairness, I might support laws that say everyone, no matter their personal beliefs, must treat LGBT people as equal citizens. But folks who rank sanctity higher than care or fairness in their value hierarchy may feel that homosexuality is “unnatural,” and that its “degradation” of sanctity therefore overrides the need for equality.

As we’ve seen recently, some folks believe face mask rules intrude on their personal freedom. They feel that their individual rights (liberty) take precedence over those of the larger community, whereas I place more value on cooperation and the health of the collective (care). I don’t think either freedom or liberty are wrong, but in certain situations, I might feel that those values need to be curtailed for the good of everyone.

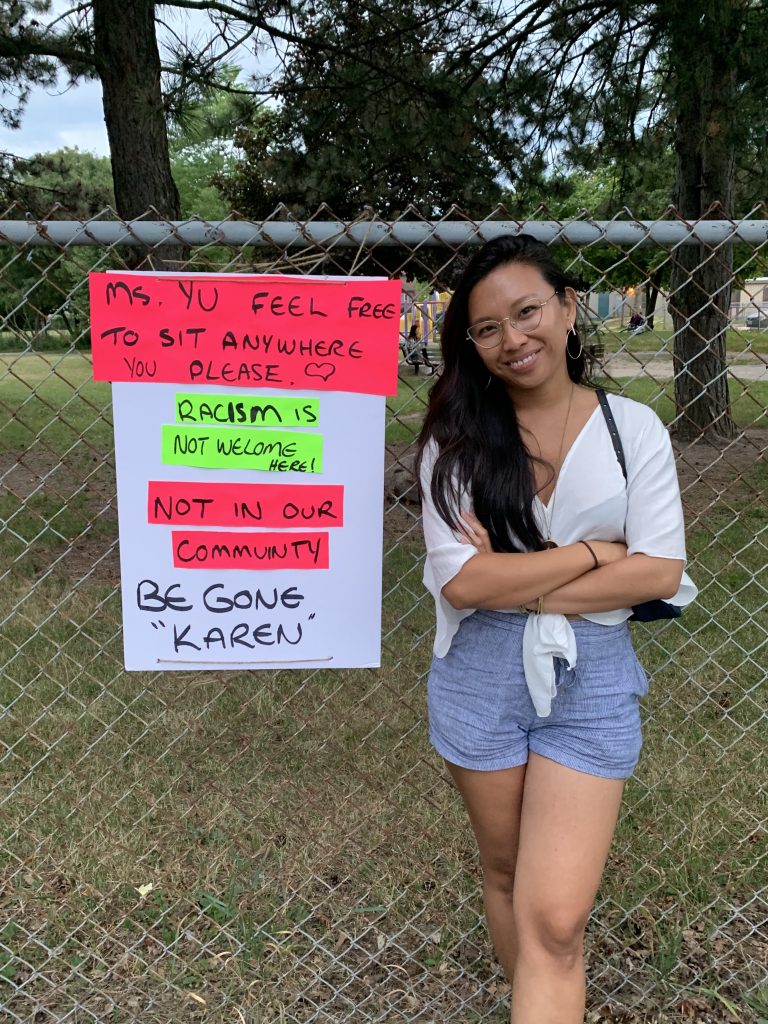

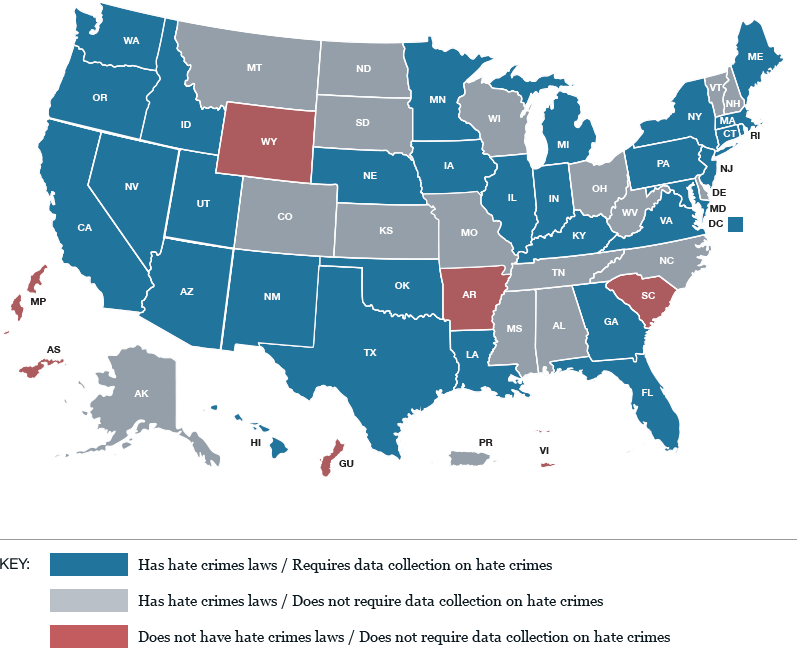

I might feel that in order to challenge unjust laws one sometimes has to break them (fairness). Others will disagree and say “the law is the law” (authority). Many Americans believe that free speech is an absolute right (liberty) and if others are hurt, offended, or feel discriminated against by what I say, well, that’s the price of freedom. In general, I personally share that value, but I don’t see it as absolute — there are times when maybe it should be regulated if it is intended to do harm or incite violence (care, fairness). The point is, I can see some worth in all of these values.

This raises an important point. The fact that all of our disparate beliefs spring from the same six values doesn’t mean all beliefs have the same merit, or even any merit at all. Prioritizing some values — like sanctity of race or homeland, in the example to follow — can justify inhuman behavior.

Adam Gopnik, writing about the Nazi “angel of death” Josef Mengle in The New Yorker, noted: “There is nothing surprising in educated people doing evil, but it is still amazing to see how fully they construct a rationale to let them do it, piling plausible reason on self-justification, until, like Mengele, they are able to look themselves in the mirror every morning with bright-eyed self-congratulation.” The point is, we shouldn’t excuse behaviors that harm others — we should simply try to understand why those behaviors happen and the mechanisms that are used to justify them. To paraphrase the writer Hannah Arendt when she was accused of justifying what the Nazis did: To understand is not to excuse.

What does all this tell us? It tells us that, though I may disagree with folks on certain issues, those disagreements are nonetheless rooted in values that they — and I, to some degree — share. Our beliefs and our politics may be very different, and yet, by recognizing the values behind them, I can, to some extent and in some instances, empathize and understand why someone might feel differently about an issue than I do. It helps me to not judge them as ignorant or evil, and gives us a foothold, a place to start a conversation.