During the pandemic I have gone on some fairly long bike rides with band members and friends, exploring parts of our city that some of us are somewhat unfamiliar with. Most of us New Yorkers have been trapped in our apartments, so getting out has been, for me at least, both enlightening and a life saver.

I organized some rides to Staten Island recently, the island borough just south of Manhattan, promising my fellow riders “a visit to the land of Trump and Wu-Tang.” That pitch is exaggerated, but not entirely untrue — Staten Island has earned its conservative reputation — but of course, it’s more complicated than that. There is a whole artistic mural culture on Staten Island, and the stories on this island suggest that divides here are being bridged, and that its politics are more nuanced than they first appear.

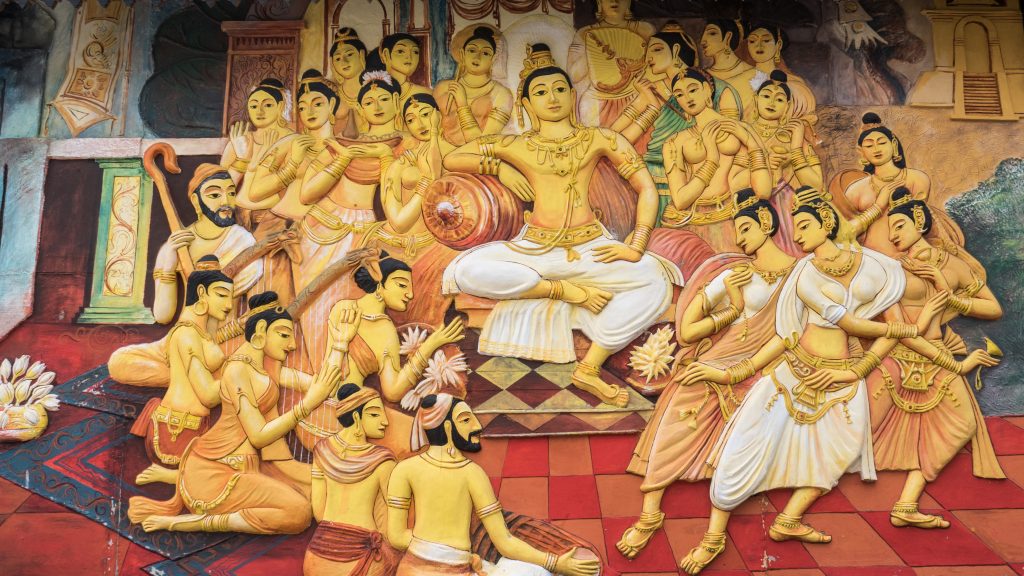

After taking the (free!) ferry from Manhattan we stopped for lunch at a Sri Lankan restaurant called Lakruwana, which has an amazing bas relief mural facing Bay Street.

The food was good, and the rest room had plaques all over with messages on them.

At least 5,000 Sri Lankans live in the northeast part of Staten Island. How’s that working out? It depends on how you look at it. Sri Lanka’s 30-year civil war only ended in 2009. In that conflict the minority Tamils fought against the Sinhalese-dominated government after being stripped of citizenship, though they had been living there for hundreds of years. The “Tamil Tigers” were guilty of frequent bombings, and the Sinhalese government was likewise accused of committing many human rights abuses including bombing civilian targets. It was nasty all around.

Sometimes when folks immigrate from a conflict area, they bring their old rivalries with them, and end up living cheek by jowl with their former enemies in their new adopted home. This can mean these two sides don’t communicate much. There’s an uncomfortable silence. But food can be a bridge. Customers at the restaurants here come from both sides of the Sri Lankan conflict. They put aside their differences to come together for the food they miss. Julia Wijesinghe, the daughter of the owners of Lakruwana, decided to go a step further. She opened a museum of Sri Lankan culture in the basement of the restaurant in 2017 — a celebration of the culture that is shared by folks on both sides of the conflict.

There are signs that the divides in the community are healing. In 2019, following a rash of horrific bombings in Sri Lanka, the Staten Island immigrants united to hold candlelight vigils to honor the dead in their homeland.

As we enjoyed our lunch we looked across the street at a building covered by a massive mural and wondered who was Charlie B, what is NYC Arts Cypher, and what is this place? Of course, there’s a story here.

The late Charlie Balducci (he passed in July) was an early reality TV star — a young artist who landed a “part” on an episode of the MTV show True Life. Stressed out over all the filming, at one point he ripped into a limo driver who was an hour late picking him up for his wedding: “[I’ll] hunt you down like fucking cattle and I’ll gut you!” Charlie later said that’s how any Staten Islander would have reacted.

But there’s another side to Charlie. He used his cash and his notoriety to start NYC Arts Cypher, the non-profit in this building, where he and others mentored young artists. The organization confronts social issues like bullying and drug use, and trains the kids in branding, design and how to make a living doing legal street art. Those murals we saw everywhere. One way they raise funds is through an annual Halloween haunted house in the building. One of the folks sitting outside in the picture above told me that the haunted house is still on this year, and that there would be “stuff jumpin’ out at ya.”

So Charlie is maybe not the cliched reality star some of us might at first assume. This guy really did something incredible with a lot of heart, and it’s still going.

Then we headed back inland, passing by a lot of wild turkeys. WTF! Apparently there are over 250 of them on the island. At first we thought: a nice Thanksgiving dinner maybe? But I wouldn’t mess with them — they’re big, and like true Staten Islanders, they didn’t seem afraid of us at all.

Nice lucky segue here from turkeys to flags — there are a LOT of flag murals on Staten Island. Some of us saw them as dog whistles for Trump supporters. While sticking up a Trump sign in NYC might get you some looks, who could argue with the flag?

It turns out there’s a story here too. As reported in The New Yorker, many of these flag murals were painted by a local artist, Scott LoBaido, and yes, he’s a Trump supporter. But once again, it’s a little more nuanced than that.

“He says that he has painted at least three flag murals in every one of the fifty states. The acquaintance asked whether he paints Confederate flags. “No,” LoBaido answered immediately. He raised his Martini glass to salute a driver who was saluting him with a Dunkin’ Donuts cup through the open window of a pickup truck. “I can’t say I would never paint any particular thing,” he went on. “But a Confederate flag? No. I know some people say it’s not racist, it’s about Southern heritage. But I’ve never painted a Confederate flag. It’s nothing like the American flag. The American flag is the greatest work in the history of art, because it’s about everybody—Blacks, whites, every immigrant, every person who dreams about this country. It’s about me, it’s about you even though I know you don’t agree with me politically”

This gives me hope, hearing a Trump supporter say that the flag represents a country that is open to people of every race and background. It just goes to show that things are sometimes a little more complex than I might at first assume.

We took Old Town Road (!) on into the neighborhood of Richmond until we came upon a mural proclaiming the area to be the Wu-Tang District. Yup, last year the borough made it official. At the event inaugurating the new district, Ghostface Killah said, “I never saw this day coming. I knew we were some ill MCs, but I didn’t know that it’d take it this far.”

The projects depicted on the mural are just off to the right. The right side of the mural now incorporates a memorial made of painted cinder blocks.

So, Staten Island seems to be, in some ways, a lot more nuanced than my snobby Manhattan biases might have led me to believe. Check your attitude, David! It’s a work in progress for sure — how these communities can get along. But even in these brief trips I learned that things aren’t as black and white as I first assumed. These trips we take aren’t just good exercise and a way of getting out of the house, they change the way I see things.