The message often heard in America is that liberals want to do something about climate change and conservatives do not. But what if it’s not that simple?

If you look at the polls, most Americans — on the left and the right — think that climate change is a serious problem we need to deal with. But the structure of the political system, the influence of money in politics and the warping effect of polarization have bifurcated the issue along party lines, making it nearly impossible to take necessary action. In our latest interview with researchers from Stanford University’s Polarization and Social Change Lab, Samy Sekar explains how even an undeniable crisis can get caught in the web of money and politics, and how institutional change could break it free.

![]() This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell us about yourself.

I just completed my PhD in environment and resources at Stanford University. Specifically, I was trying to understand what was causing the misrepresentation of Americans’ attitudes at the state and federal policy level when it comes to climate change.

Is there any debate to be had about climate change at all?

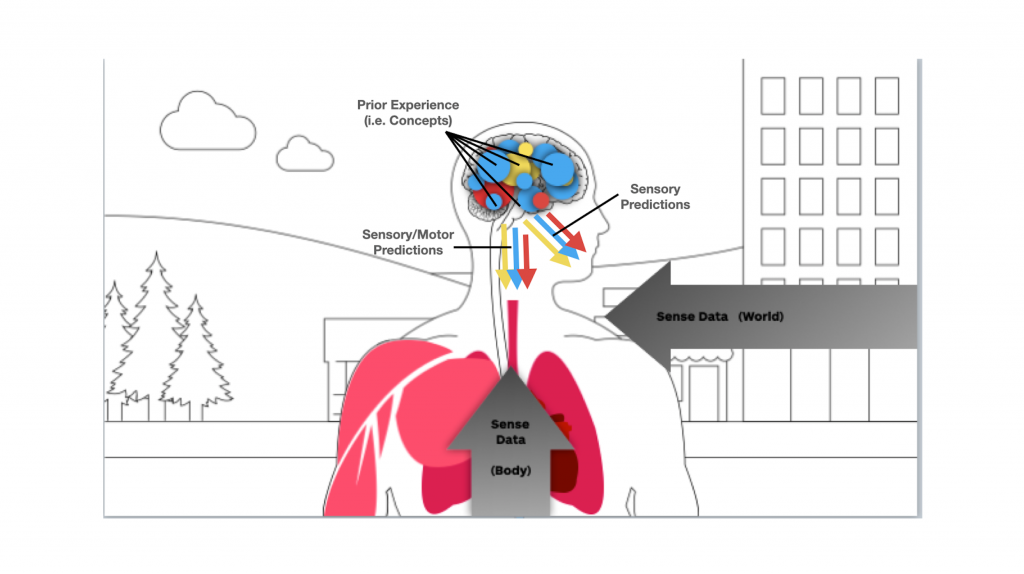

It is beyond a reasonable doubt that anthropogenic climate change is happening, and that we are causing it. Where there is room for debate about climate change is around policy: How should the government address it? How much should it spend trying to address it? Who should pay the cost of addressing it? A whole slew of policy issues can be debated, but the phenomenon itself can’t be debated.

There’s a commercial from 2008 featuring Newt Gingrich and Nancy Pelosi sitting side by side on a couch, saying, “We don’t always see eye-to-eye, but we do agree our country must take action to address climate change.” These days, Newt Gingrich is a climate change skeptic, and the word “climate” doesn’t appear once in the Republican Party’s platform. What does this say about how politics can change politicians’ views (or, at least, their messages) about climate change?

More than 70 percent of Americans believe that climate change has happened. And most [of those people] have believed that climate change is human-caused. In a 2018 study by Stanford’s Jon Krosnick’s lab, the political psychology research group found that 78 percent of Americans support some sort of government action on climate change.

The fact that a huge number of members of Congress and our president don’t believe in climate change, or claim that climate change isn’t happening or that it’s a hoax, is not representative of the American public’s views.

There’s a name for this mismatch that occurs when an issue is polarizing within institutions, but is broadly agreed upon by the public: “democratic deficit.” Can you talk about this?

A paper by David Brockman and Chris Gavron found that both Republicans and Democrats at a state legislator level were actually less progressive in their policy views than their constituents. And there was a study in 2019 that showed something similar at a federal level when it came to congressional staffers predicting their constituents’ views. They were asked, “What percent of your constituents do you believe want the government to reduce CO2 emissions?” and similar questions about health care and other policies. That paper by Fernandez, Stokes and Miltenberger found congressional staffers were underestimating how progressive their constituents were.

There are a few different reasons why this democratic deficit could exist. One reason could be that people have policy preferences, but those policy preferences don’t necessarily map on to how people vote for their representatives.

Alternatively, you could vote for a politician that theoretically supports [your policy preference], but then you and all of your fellow constituents don’t voice your opinion loud enough for them to hear what you want.

What causes this disconnect?

What you find is that the congressional staffers who most poorly predicted what their constituents wanted were the ones who are getting the most visits from lobbyists. That means they’re getting signals about what companies in their districts want that may be louder than the signals they’re getting from their constituents.

Where does the climate fall on the priority lists of voters?

There was a survey done by the political psychology research group at Stanford and [the nonprofit] Resources for the Future. It was the 20th or 25th year in a row that they ran the same climate change survey. They found that the percentage of Americans who say climate change is extremely important to them personally is higher than ever.

There aren’t a lot of options if you want to vote for a Republican who is passionate about climate change. While there is some polarization on the climate change issue among the American populace, there is extreme polarization on the climate change issue among American legislators or politicians.

So if you’re a Republican who is very passionate about climate change, you can either have your general worldview represented in the context of electing a Republican, or you have to have your climate preference represented in the context of electing a Democrat [who supports] climate change.

The small number of options there were for Republican climate voters, they are losing because of political polarization.

How strongly does polarization drive the actions of both voters and politicians?

One problem with political polarization is the competition ends up being not between the two parties, but within each party. There are people who are perhaps willing to sit out the election because they don’t believe that Joe Biden is going to take climate change seriously enough. It’s not because the other candidate is going to take climate change more seriously, it’s simply because in the primary, their candidate who was more serious on climate change lost.

But because affective polarization is so strong, the majority of Democrats, even if they think Joe Biden doesn’t represent them or their views, will vote for him because they hate the other person and other party. There is a competition of ideas within the Democratic party and then whoever wins that competition gets the support of the vast majority of Democrats.

Any given issue gets swept under the rug when people are holding their nose and voting for the less bad of two candidates. It’s very obvious at the presidential level. I’m less certain it’s happening at the congressional level because you see progressive candidates beating out centrist Democrats because of their progressive stances on many issues. The Green New Deal has been front and center almost every time.

So what would it take to create a major policy shift?

About five or six years ago there appeared to be some hope among economists and natural scientists that a bipartisan climate policy was possible. Now, because parts of the Republican Party with particularly extreme views on climate change have won out, and because progressives and Democrats have started to expect more urgency from their leaders in addressing the crisis, a bipartisan solution seems further away than ever.

If you were to ask Republican voters, “Do you believe climate change is happening? Do you believe that it’s human-caused? Or at least partly human-caused?” you will still get about 50 percent to 60 percent of Republicans saying yes to those questions. It could be that the remaining 40 percent are the loudest 40 percent, but I think there’s another component, which is lobbyists and all of these other things that elevate the voices of a small percentage of the Republican party or Republican voters.

If you had a magic wand, what institutional changes would you make to increase the likelihood of passing climate policy?

My research has shown that Republican state policymakers are willing to update their policy preference to be more in line with their constituents’ climate mitigation policy preference. So my view on how this could change is to start at the state level — pass strong, stringent climate policy at the state level, as we’ve seen in New York.

One key component to make serious climate policy more likely at the federal level is reducing the extent to which lobbyists can knock on any member of Congress’s door and influence their beliefs and attitudes.

Essentially, [overturning] Citizens United, money in politics, lobbyists in politics — the extent to which we can reduce that, I think that is the biggest barrier to implementing or passing climate policy.

Another thing we’re seeing at an extreme level in this election is making it harder to vote. We’ve seen it over and over again that the American people really want this climate policy. [It would help] if we made it easier for them to vote [instead of] making it harder to actually cast a ballot without a voter ID or without waiting in line for 10 hours without getting sick.

Giving people Election Day off and having more people vote the way Australia does [Australia has compulsory voting] would be excellent mechanisms. Getting the people’s voices heard more clearly is a key factor.

Ultimately, my argument is that the people’s will isn’t being represented because the political elite are more polarized than the people themselves are on specific issues. If you made it easier for a third-party candidate to get into the mix, that would make it easier for a Republican to choose someone that actually aligns with their views on some issues, but who is also not a Democrat.