Polarization occurs over the course of decades, across regions, races and generations, between parties and people. But there is one common thread: it always inflames emotions.

Luiza Santos, a third-year PhD psychology student at Stanford University, specializes in affective science — simply put, the study of emotion. In this final interview in our discussion series with researchers from Stanford’s Polarization and Social Change Lab, she dives into polarization as it manifests in our brains: the ways it makes us feel and act, and what we can do about it. We discuss how empathy works, its role in political discourse and resisting the temptation to hate the other side.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your work centers around empathy and how it plays out in politics and everyday life. Can you walk us through the psychology of it?

Empathy has a lot of multi-components, but one of them is empathic concern. So if I see that you’re suffering, I feel bad for you. The other one is perspective-taking, and this is a more cognitive side of empathy where you put on the shoes of someone in that experience and try to live through how that experience would feel.

Even though they’re related and there’s some overlap, they can have different consequences. I try to understand what motivates a person to empathize with outgroup members or what keeps people from empathizing, and understand how we can change people’s beliefs about empathy.

What do the terms ingroup and outgroup mean?

An ingroup member is a person who thinks like you and shares some sort of belief structure that you also share. An outgroup member is a person who does not. This ingroup-outgroup relationship becomes more salient in competitive environments. If you’re a liberal, your ingroup would be other liberals. If you’re a conservative, your ingroup would be other conservatives.

Things like threats can activate different sorts of groups. If we think about terrorism and terrorist attacks, that causes what pychologists call the “rally-round-the-flag effect” where basically distinctions between liberals and conservatives kind of disappear because they all cluster together around this American national identity instead of being divided on politics.

Not every disagreement is a fight or a threat, but they can feel that way, especially in politics. How do our brains distinguish between disagreement and threats?

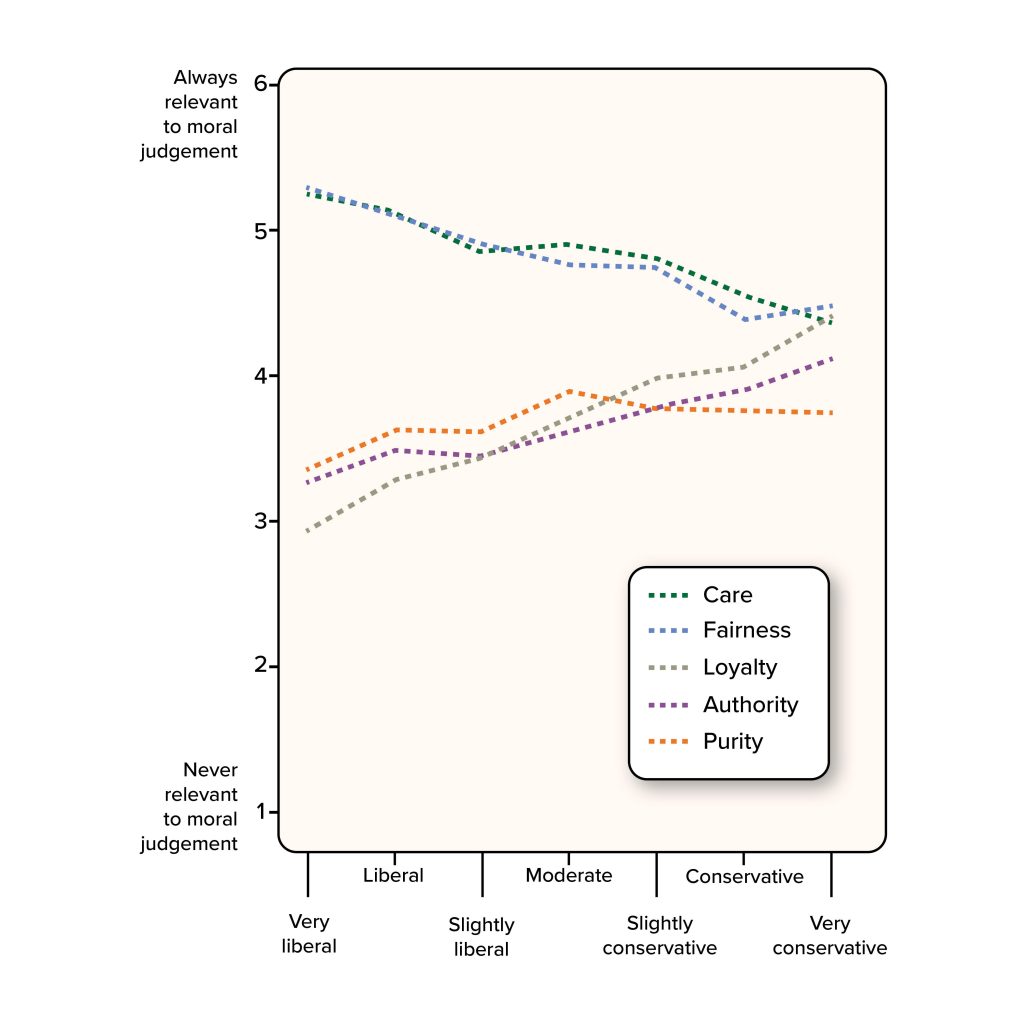

Some of my research interests try to understand how attitudes become moralized. If someone comes to me and says they don’t like chocolate ice cream, I’m like, okay, that’s their own personal opinion. But if we think [in terms of] moral values and I think it’s wrong to kill people, and you come to me and you say it’s okay [to kill people], I would be like, this person is amoral. So there’s these different spectra of disagreements, from those where you could see potential compromise to those that you feel are really infringing on your central beliefs about right and wrong.

Empathy can seem like a natural emotion, so why does being challenged or proven wrong feel so unnatural and exhausting?

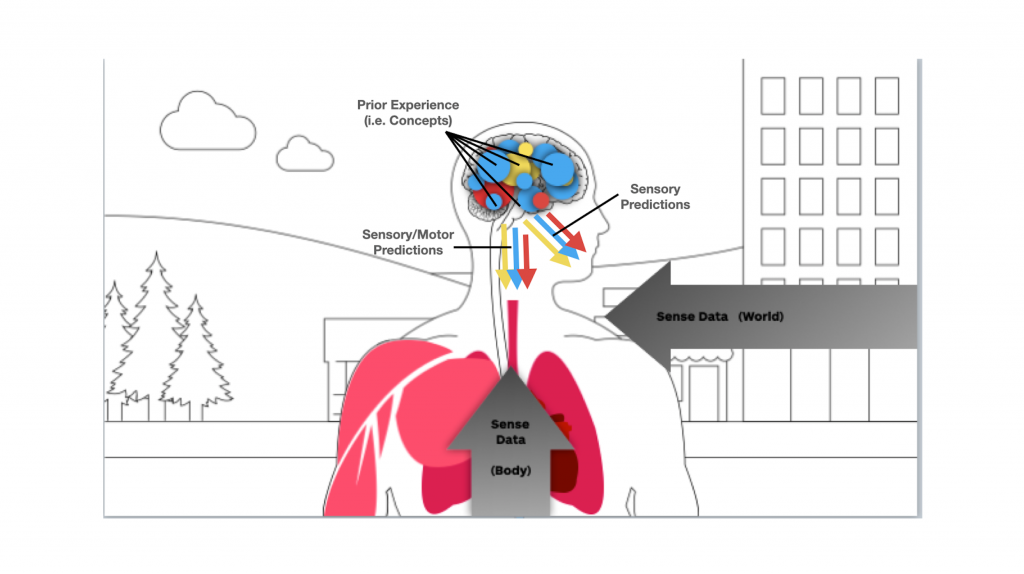

Empathy is this superhuman power that we have to try to understand the mind and beliefs of someone who could be radically different from us. The problem is that it doesn’t happen naturally. People have talked about empathy as this automatic mechanism, and we can totally see this where that’s true. Infants will cry when they hear another infant crying. Or we can care for completely fictional characters as we read a novel. There are all these ways empathy feels natural and automatic. But then when we look at ingroup and outgroup processes and see that’s not really how it happens.

If it’s not completely automatic and we have some control over it, then we can choose how we empathize in certain circumstances. It may feel very effortful, especially when you’re trying to empathize with someone who endorses beliefs that you find fundamentally wrong. One approach we’ve been taking — and that some recent research is trying to investigate — is the reasons why people try to avoid empathizing with outgroup members. Those reasons include things like, ‘I think their views are threatening to how I see the world.’ Or, ‘I think if I empathize with them, people in my group would see me less positively because I’ll be betraying my group.’

We try to investigate the motivations people may have that can lead them to either choose to empathize or avoid empathizing.

Could empathy have a downside? For instance, could it be used to simply paper over the problems that are causing a lot of the animus and polarization in our world?

My main rebuttal to that is sometimes we get so in depth into our group membership that we start seeing division where once there wasn’t any. If you feel that your identity is under threat by someone else’s belief, I see the point of believing it’s not your job to go out of your way to try to change a person’s view. But I do think at a greater society level, if we say that it’s not worth trying [to have a conversation], you consolidate these thoughts in a way that can be really harmful down the line. It pushes people to find niche groups that agree with them. The internet is a whole new world for that, and then you only find echo chambers.

So is having open and empathic conversations always worth the effort?

I just feel there’s no alternative. Being in a group has many benefits and gives us certainty, and when the world is kind of uncertain, it helps to guide our beliefs. But at the same time, it’s important to take a step back and understand that we’re all members of a broader group.

We’re all super tired. It’s hard to have family members that you grew up with and now you feel like you can’t talk to anymore. It’s emotionally exhausting to try. But I do believe that it makes a difference, even though sometimes it’s one conversation and one person. Having uncomfortable conversations where you try to be open-minded and then voice your concerns is one way to grow and understand different perspectives. It never ceases to be uncomfortable, but it’s still worth a try.