Justine Abigail Yu was sitting alone in the school yard of a Toronto public school this summer when a white woman came up to her and told her she had to leave: this was private property and Yu was trespassing. Yu was confused. This was a space she had been to many times before and seen families set up picnics and bring their kids to play on the playground. So Yu thanked the woman but decided to stay and keep reading. “I’m going to call the police on you if you don’t… I’m a teacher. There are signs here that say, ‘No Trespassing,’” Yu says the woman insisted. “Can you read or maybe you don’t speak English?… Go back to China.”

Yu was stunned. After the woman walked away, Yu decided to turn on her camera and recount what happened before she forgot the details. That’s when Yu caught the woman saying back to her, “All Chinese people should go to jail.”

Yu, a Filipina-Canadian, is one of many racialized people who have been the target of racist attacks; sometimes verbal, sometimes violent and sometimes caught on camera. After she was targeted, Yu wasn’t sure exactly how to report what happened. She asked herself, “Can I even file a police report on that? What does that count under?” While some statistics are kept by law enforcement agencies, the numbers often don’t include the everyday reality for people of color. Racialized people have a long history of being targeted by authorities and may not feel safe reporting to police. Police could be the group causing the harm, there can be language barriers and, even if reported, not all incidents will meet the threshold of a crime.

But increasingly, grassroots organizations across North America are collecting data in that gray zone. That data is now becoming a crucial part of shaping solutions, supporting advocacy, changing laws and strengthening allyship.

On a Zoom webinar with almost 1,000 people watching live, Hollaback! trainer Jorge Arteaga starts introducing himself. He’s Afro-Latino and, unsurprisingly, has a personal story of how he was wrongfully targeted by police as a teenager. After sharing, he takes a deep breath and pauses before delivering an hour-long bystander intervention training on how to stop police-sponsored violence and anti-Black harassment.

“It’s a little nerve wracking for me,” says Arteaga, who is also the director of operations at Hollaback! “But what I’m thinking in my mind is … what story can I share so that, you know, this whole experience kind of resonates with people so that when they walk out of the training, they go out on the street and they’re ready to use one of the five Ds.”

Arteaga shares how bystanders can intervene if they see someone being targeted — a technique known as the “5Ds”: directly addressing the attacker, offering a distraction, delaying and offering support, delegating by getting help from people around you or documenting the incident.

Their bystander training has evolved over time and has been influenced by stories from the community and data. In 2014, Hollaback! teamed up with researchers at Cornell University to launch a large-scale research survey on street harassment. It spanned 42 cities in 22 countries and had over 16,600 respondents, making it the largest analysis of street harassment at the time.

“One of the common denominators they found in the stories was that people wished someone was there to help them when they were experiencing harassment, or that somebody would have jumped in to do something,” says Arteaga. “So based on that Hollaback! was like, okay, bystander intervention, that’s the path that we need to be exploring.”

Today, Hollaback! continues to collect stories of people who have experienced harassment. They monitor the news and adapt the bystander training in collaboration with different communities. They’ve since adapted trainings to address harassment towards Asian-Americans and the LGBTQ community, and are developing one to address state-sponsored violence towards immigrant communities. Arteaga describes their model as a “perpetual front to harassment.”

Between April and June, 2020, in response to Covid-19 and #BlackLivesMatter, Hollaback! trained over 12,000 people on what to do if they see anti-Asian racism, and over 4,000 people on police violence and anti-Black racism. Ninety-nine percent of respondents surveyed come out of the training saying they feel equipped to do at least one thing to help if they witness a racist incident.

Yu wanted accountability and also felt like she had a responsibility to her BIPOC community to share her experience, so she posted her story and video on social media. Incidents like the one she experienced happen frequently, says Yu. “Black, Indigenous, people of color are constantly called into question for doing anything — for even just belonging here on this land.”

Her post got over 1,400 shares and likes. She was able to identify the woman (but is not publicly sharing) and people suggested she report her experience to different community organizations that track racism including the Canadian Anti-racism Network, Act2endRacism, Iamnotavirus.net and Fight Covid Racism.

With this kind of data, organizations like these are able to develop specific resources, launch targeted education campaigns, research geographic trends and advocate for legislative changes.

“These kind of data definitely help us talk to our leaders about how these instances are continuing to happen and it needs to be addressed,” says James Woo, who oversees communications at Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta. Advancing Justice is made up of five organizations across the U.S., advocating for the civil and human rights of Asian Americans.

Advancing Justice’s Stand Against Hatred website has been tracking hate crimes against Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the United States since 2017. It invites people to share their experiences and provides reporting forms in a variety of languages including Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese. The goal, Woo says, is to provide a “much better picture” of reality.

FBI data is supposed to be the most comprehensive but it doesn’t really capture the experiences of racialized people’s daily lives, says Woo. Barriers to reporting include language, mistrust and fear of authorities, and the varying reporting procedures for hate crimes in each state.

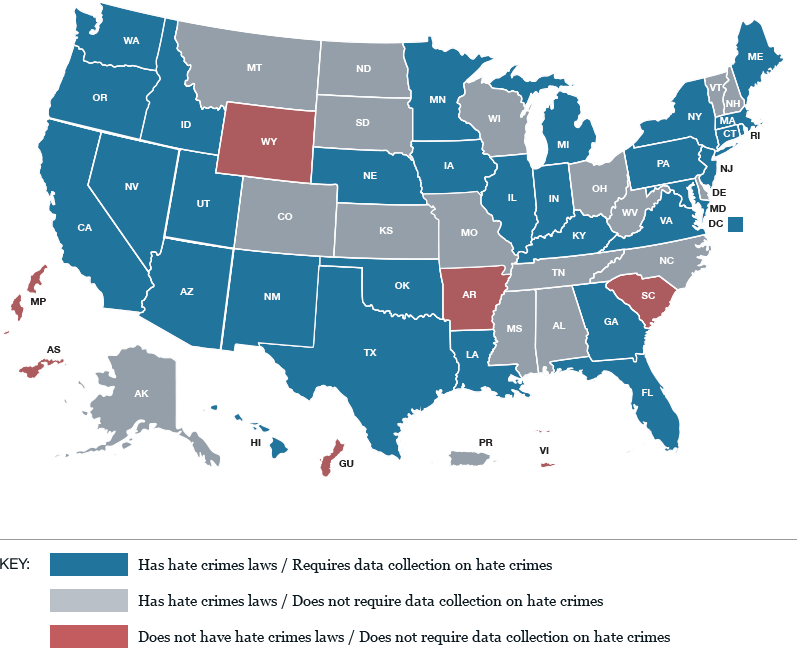

“There are a lot of policies and rules that are really hurtful to Asian-Americans or immigrants in general,” says Woo. The state of Georgia, for example, only just signed a hate crimes bill into law this June. Wyoming, Arkansas, and South Carolina still do not have any specific laws that cover crimes motivated by a person’s race, religion, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability. And, despite having laws, more than a dozen states do not require any data collection on hate crimes.

Woo says that Advancing Justice wanted to make sure that Asian American and Pacific Islander voices were included as the bill in Georgia was developed, so they shared their data with legislatures. The data has to go beyond just being collected, says Woo. “We are trying to actively utilize the data to make actual policy changes.”

For Justine Yu, no one was around to step in or be a witness. And while she hates to admit she was scared, she thinks that having a witness or someone around could have eased her tension. “I felt really, I don’t know, just nervous about the fact that, if she does call the police, what does happen?” she said. “I started, at some point in those moments, questioning whether or not I was within my rights to be there.”

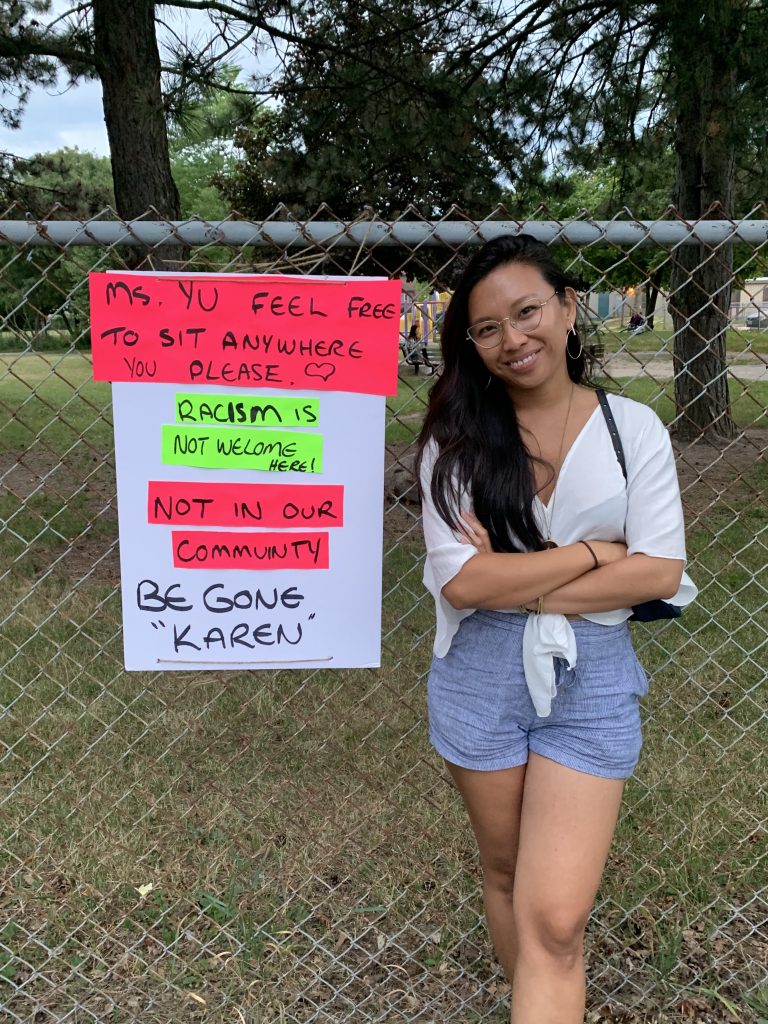

But when Yu returned to the park with her partner a few days later, she found that the neighborhood had put up signs of support. “Ms. Yu, feel free to sit anywhere you please. Racism is not welcome here!” read one sign.

“Those signs almost felt like some sort of protection,” said Yu. “If I ever did have to encounter this woman, hopefully there would be people around who would mobilize or would feel compelled to say something and to do something in that moment should anything else happen.”