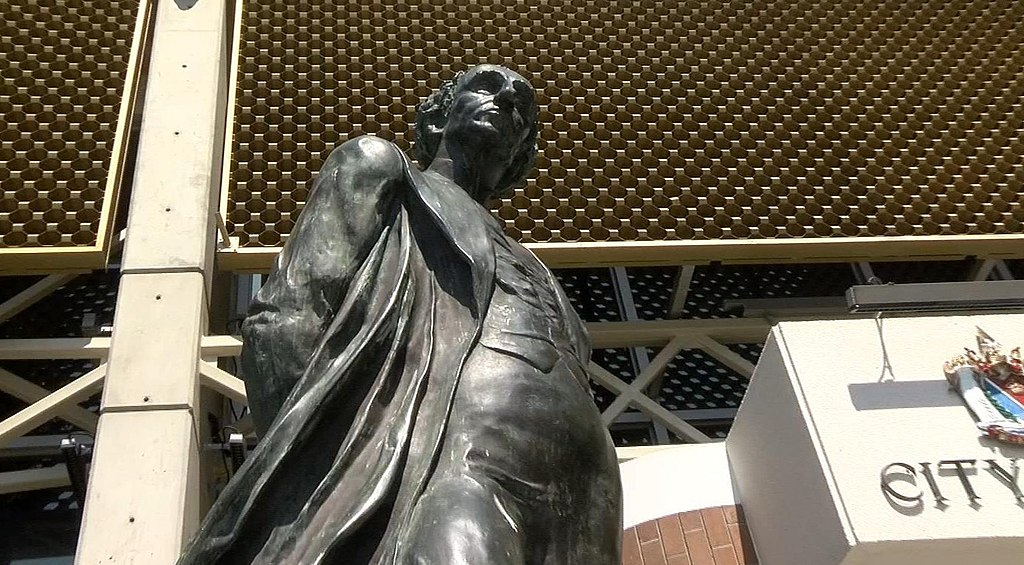

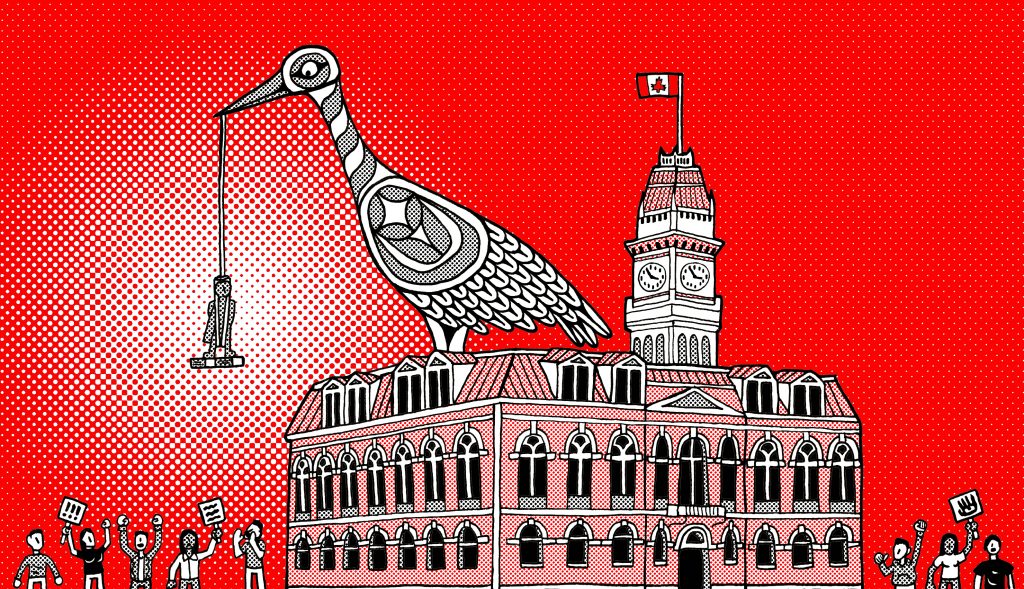

At 5 a.m. on August 11, 2018, city workers in yellow vests and hard hats arrived at City Hall in Victoria, British Columbia. It was a cloudy morning in the small coastal provincial capital, and even at the early hour a crowd was gathering. The workers flanked a bronze statue of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, which stood behind a tall metal fence. Cinching ropes around Macdonald’s neck as the sun broke through the clouds, they hoisted the figure off its base.

As the statue swung toward a waiting flatbed truck, a dozen protesters linked arms, singing the Canadian national anthem. A handful of counter activists responded with their own chant: “Na na na na, na na na na, hey hey hey, goodbye!”

At 7:30 a.m. the truck pulled away with its burden, on its way to placing the nation’s founding father in the hidden confines of a city storage facility.

Macdonald’s Victoria likeness joins a growing heap of discarded monuments to controversial figures around the world: Violent colonialists. Slave traders. Genocidal politicians.

In 2015, after a long and emotional “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign led by Black South Africans, the University of Cape Town toppled a statue of famed imperialist Cecil Rhodes, whose policies laid the foundations for Apartheid. That same year, a movement to do away with U.S. confederate monuments gained traction. By 2018, more than 100 of them had been plucked from their former places of pride and many others faced harsh scrutiny.

This moment peaked when the Charlottesville, Virginia city council voted in favor of removing a statue of Confederate Civil War general Robert E. Lee, sparking an infamous eruption in the streets between white nationalist groups and counter protesters. The feud climaxed when right-wing extremist James Fields drove his car into the crowd, hospitalizing 19 people and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer, a supporter of the removal. Fields pled guilty to 29 charges of hate crimes and was sentenced to life plus 419 years in prison. Charlottesville’s monument to Lee is still standing.

Since June this year, Charlottesville’s Lee statue and countless other monuments around the world have come under renewed scrutiny amid global anti-racism protests. Hundreds of statues have been removed almost overnight by city governments, or dealt with by protestors: smeared with red paint, toppled from their podiums, beheaded.

Yet few of the cities where these statues have fallen have deeper plans to address the roots of these interventions, as though removing the visible symbol of racism or hatred — the monument — somehow absolves the city of the duty to deal with that problem further. For example, “Many of the cities that have made symbolic gestures in support of Black activists and communities in recent weeks have also declined to cut police budgets as drastically as activists had hoped,” the Boston Globe reported.

More than ever, it seems, the world is desperate for a how-to guide for taking statue removal beyond the symbol, to the system. That’s what makes Victoria’s story special.

Bill Stewart is Métis, a term which refers to people of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry or, in a legal context, descendants of specific communities in Ontario and the Prairies.

Stewart had publicly advocated for the removal of Macdonald’s statue from Victoria City Hall. When he arrived at the scene shortly after it had been removed, someone showed him a picture of the statue hoisted by its neck.

He immediately thought of the historic Métis leader Louis Riel, who was hanged for treason by Macdonald’s government in 1885 for leading an uprising to defend Métis and First Nations rights. “It was a symbolic hanging,” Stewart says of the statue.

Stewart, who is 54, was taken from his birth mother as a newborn and adopted into a white family in Kitchener, Ontario. He only discovered he was Métis in his twenties, after years of abuse from his adoptive mother.

“I spent the majority of my life seeing myself as a white man,” explains Stewart, but “I was raised being discriminated against for being Métis.”

Stewart wouldn’t understand the full implications of his Métis identity for another 20 years after his discovery. Upon meeting several survivors of the “Sixties Scoop” — an assimilationist child welfare practice in Canada, where at least 20,000 young First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were taken from their families and adopted into other, predominantly white, households — Stewart realized he, too, had survived the Scoop.

Many of the figures whose statues have been felled in recent years represent colonial power exerted ruthlessly and violently. But Sir John A. MacDonald, Canada’s schoolchildren have been taught to understand, embodied a different ethos.

In national lore, Macdonald has been portrayed as the gentle if imperfect George Washington of Canada and a deal-maker with mother England. Textbooks praise him as the person most responsible for uniting Canada under confederation in 1867 and building a transcontinental railroad when few thought it possible.

What Canadian schools have not taught until recently — a change accelerated by specific requests from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission — is that confederation was achieved on the backs of Indigenous people, whose culture Macdonald worked to explicitly destroy as Canada’s longest-serving superintendent-general of Indian Affairs. He pushed forward the Indian Residential School System and the Department of Indian Affairs, the foundations of Canada’s assimilationist policies, with the explicit aim to eradicate Indigenous culture and “get rid of the Indian problem.”

Last year the federally funded Canadian Museum of Human Rights recognized that the Indian Residential Schools system, which ran until the final school closed in Saskatchewan in 1996, was a violation of the United Nations Genocide Convention.

The Sixties Scoop (which lasted officially until the 1990s, and some argue continues unofficially to this day) was an extension of that system: In both programs, the practice was to remove Indigenous children from their homes at a young age, often without parental consent, while they could still be “civilized” and taught Western ways, as the then-Minister of Public Works Hector Langevin told the House of Commons in 1883.

For Stewart, a monument paying homage to Macdonald is “not an academic issue. It’s something that strikes very close to home.”

Protesters on the day of the removal included members of the white extremist group Soldiers of Odin and the hard-right BC Proud group. But many with less radical leanings also take their side.

A national survey found that 55 percent of Canadians opposed the statue’s removal, twice as many as those who supported it. Seven in 10 Canadians believe “the name and image of John A. Macdonald should remain in public view,” the survey also found.

The heated debate sparked by the statue’s removal did not surprise Reuben Rose-Redwood, an associate professor of geography at the University of Victoria. “Statues in particular are these focal points for conflicts over culture and values,” says Rose-Redwood, who has spent the past decade publishing research about “commemorative landscapes” — physical signs and statues which memorialize, and often celebrate, certain people, events, or values. “It’s taking our values, which are this intangible thing, and materializing it in the actual landscape,” he adds. It gives us somewhere tangible to point to, or go, to fight over these values in the real world.

Rose-Redwood also argues that monuments prohibit nuance. “When you place an individual on a pedestal in public space, it makes it very difficult to tell a complex narrative about that individual. The focus is on honoring them and glorifying their legacy,” he says. Certain values that may be unjust or otherwise outdated “become part of the landscape. They become taken for granted and normalized. We’re placing our values literally in stone.”

Rose-Redwood was in attendance as Macdonald’s monument was carted away. He held a sign reading: “We aren’t erasing history, we’re making it.”

The claim that removing a statue is erasing history has become a central refrain among those who object to similar actions around the world. Scholars of memorialization are quick to counter this claim emphasizing that statues are not history in and of themselves.

“Debates over statues and monuments are often framed in terms of being about the past,” Rose-Redwood explains. “I would argue they’re more about the present, and what values we want to continue forward with into the future.”

The statue of Macdonald is a prime example of this: it was only erected 38 years ago, in 1982, in a city he had only visited once, and was unilaterally approved by a conservative mayor confident the act would win support.

Historian and University of Manitoba professor Adele Perry wrote in an op-ed for the Winnipeg Free Press that it was not until the 1960s and 1970s that Canadians began to commemorate Macdonald as the founder of Canada. Macdonald’s face didn’t even appear on the ten dollar bill until 1971.

Perry argues that these commemorative acts at this time in Canada’s history “mainly tell us about the aspirations and anxieties of some English-speaking Canadians” during a period “marked by Québécois nationalism, Indigenous resistance, the challenges of feminism and a Canada that was less and less white.”

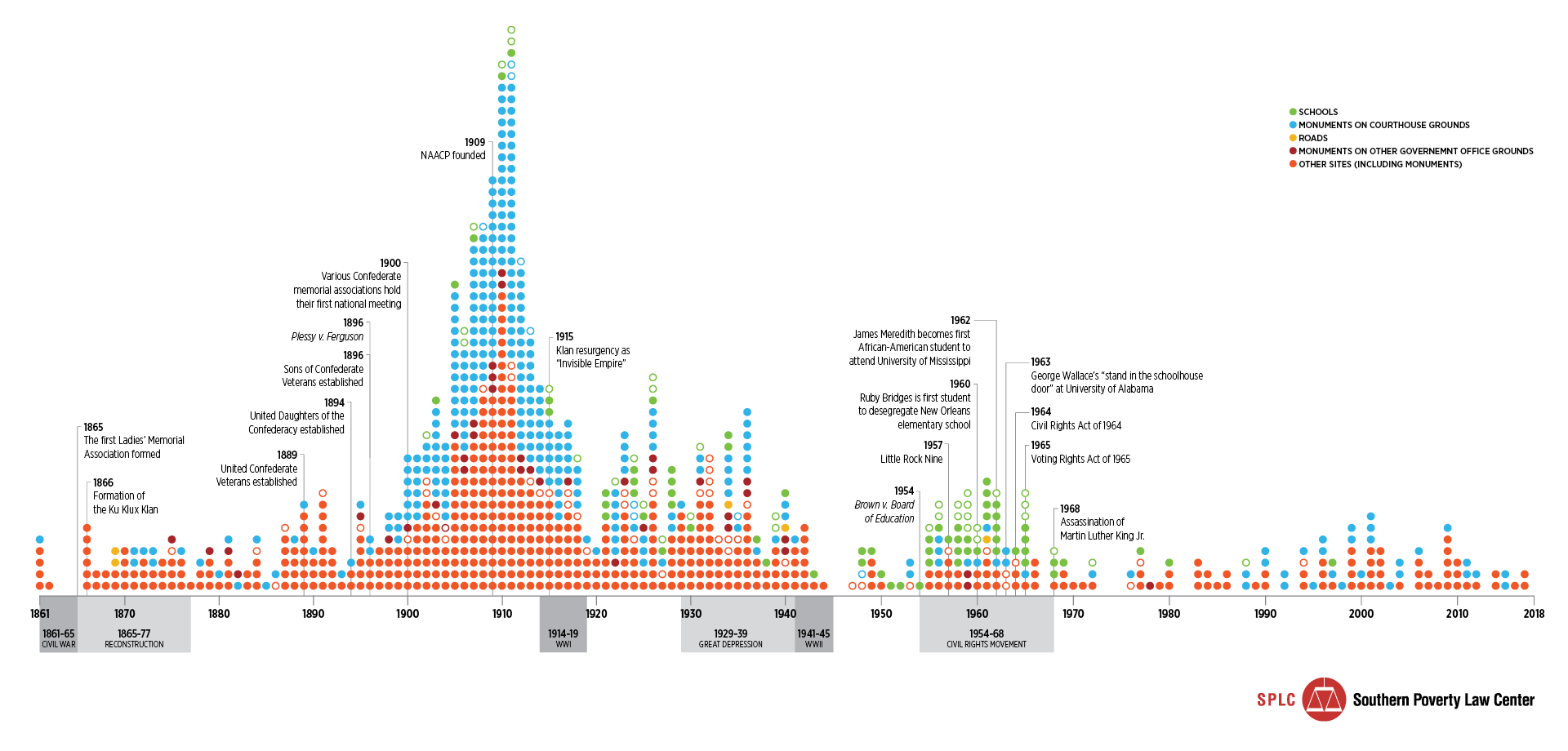

Similar belated commemoration practices forcing a certain narrative of the past during periods of unrest are common around the world. In the United States, most of the early commemorative statues erected immediately following the Civil War were general memorials to the fallen soldiers from both sides. A report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, however, shows most of the Confederate monuments now hotly contested weren’t installed until two key points in American history: during the Jim Crow Era in the South, and at the peak of the Civil Rights movement. The statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, for example, was erected more than five decades after his death, in 1924, in the Jim Crow South.

“I think it’s important to understand that one of the meanings of these monuments when they’re put up, is to try to settle the meaning of the war,” Jane Dailey, an associate professor of history at the University of Chicago, told NPR. “But also the shape of the future, by saying that elite Southern whites are in control and are going to build monuments to themselves effectively.”

Bill Stewart’s mission to see John A. Macdonald toppled in Victoria reached a very public moment at a City Council meeting on September 21, 2017.

In his pocket was a speech he’d carefully written. “I completely scrapped it,” he says, because that same day Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau had made his points more grandly, and more forcefully, in front of the United Nations General Assembly. Instead, Stewart told Victoria’s politicians what Trudeau had told the world.

“Canada is built on the ancestral land of Indigenous Peoples,” Trudeau began, “but regrettably, it’s also a country that came into being without the meaningful participation of those who were there first… For Indigenous Peoples in Canada, the experience was mostly one of humiliation, neglect and abuse.”

“The failure of successive Canadian governments to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada is our great shame. And for many Indigenous Peoples, this lack of respect for their rights persists to this day.” Trudeau pledged that Indigenous-Canadian relations would change, promising Canada would begin to abide by the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. If Trudeau’s words were to be taken seriously, Stewart told Victoria’s city councillors, they would address the Macdonald statue outside their front door.

He wasn’t the first, or the last, to make that demand. The city had already declared 2017 the “Year of Reconciliation” with Indigenous people, including a Witness Reconciliation Program meant to facilitate dialogue between the City of Victoria and the Lekwungen People, now known as the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations.

The initiative was spearheaded by City Councillor Marianne Alto, who first suggested a task force for reconciliation with the Lekwungen People, on whose traditional lands the city sits.

But the Nations didn’t feel a task force was reflective of their culture.

Through a conversation with the chiefs and councils of the two Nations, the city realized if they were going to do the work of decolonization, they needed to find a more Indigenous method for working together. On the advice of the Songhees and Esquimalt, they created a “City Family” which would operate in a relaxed, non-hierarchical way.

The City Family has met monthly in the Mayor’s office since June 2017, and is made up of Mayor Lisa Helps, a few city councillors including Alto, and members of the Songhees, Esquimalt and urban Indigenous communities — always with more Indigenous than non-Indigenous members.

On one evening each month, the diverse members of the City Family congregate in the more relaxed part of Mayor Helps’ office. They sit on couches and chairs in a circle as they share a meal. Conversation flows with no strict agenda, and although Mayor Helps is officially the leader of this family, “No one is higher than the other,” affirms Florence Dick, a member of Songhees Nation and of the City Family since March 2019. “We come in as equal.”

It didn’t take long for the John A. Macdonald statue to arise in those early gatherings. Councillor Alto recalls that before members of the City Family had grown to know and trust each other, “there was this almost palpable sense of discomfort with some of the members.” It took a few months before someone finally asked what was wrong.

Initially one person bravely shared that every time they went to City Hall, walking past the statue of Macdonald made them “feel taken aback and uncomfortable,” Alto recounts. All the Indigenous members agreed. This started lengthy conversations among the City Family about how best to address the trauma of the statue, which lasted for about eight months.

“It was a very organic and slow-moving discussion,” says Alto. “That has been a tremendous learning experience for all of us who are not Indigenous: how unhelpful it often is to rush.”

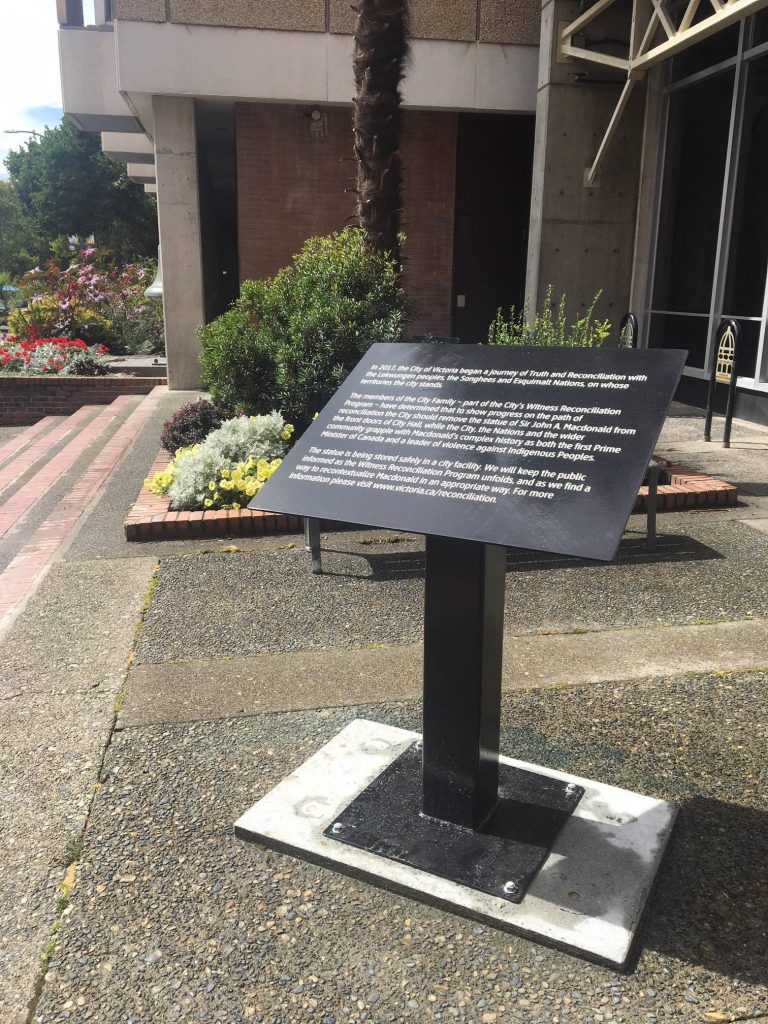

Finally, they agreed to keep the decision about removing the statue simple. They brought their idea to the local Nations’ councils for feedback and support. Everyone agreed the City of Victoria would claim responsibility for the decision to remove the statue in order to minimize the likelihood of the Indigenous people involved in the process being attacked. A plaque, co-written by the members of the City Family, would go where the statue had once stood.

“We said, we’re not going to make it happen with a lot of fanfare, we’re not going to provide an opportunity for people to become charged about this,” Councillor Alto says.

Mayor Helps is guided by the view that it’s crucial to honor the opinions of the “most deeply affected people,” in this case the local Indigenous community. Both Helps and Alto emphasize that anyone committed to tackling systemic racism or injustice or addressing a problematic monument in their community needs to think first, and constantly, about process. “You can’t just do things the way you’re used to.”

“It’s not just the act that should be reconciliatory, but also the process,” adds Helps. “The process is almost more important than the statue removal.”

This is the most pronounced difference between Victoria’s approach to toppling a contested memorial, and how it has been done elsewhere in the world. When they created the City Family, they were focused on a larger goal of reconciliation and meaningful relationship building, not the removal of Macdonald’s likeness. But when they learned they couldn’t build positive relationships as long as Macdonald loomed over their proceedings, they responded to the need voiced by every Indigenous member of their Family: that he had to go in order for the real work to begin.

When Bill Stewart heard Macdonald was losing his place of honor in Victoria, his thought was celebratory: “Wow, this is actually happening.”

Not pleased was the statue’s sculptor, John Dann. In an opinion piece he wrote for the Globe and Mail, he argued that while he was concerned about the treatment of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, removing his statue was the wrong way to address Macdonald’s legacy.

“The piece was conceived without a pedestal and it was placed in a somewhat enclosed space that facilitated an intimacy with it,” Dann wrote. “It did not aggrandize the man, but was a reflection of his humanity, on our shared humanity, with all its strengths, weaknesses, confidence and insecurities.”

For Florence Dick, the uniting of Canada into a single nation was not a noble act led by a flawed man, but a calamity of subjugation for Indigenous Peoples. Macdonald’s bronze presence at City Hall inflicted a repeated insult to her mind and soul.

“Every time we went there, it still didn’t feel comfortable. It still didn’t feel right,” she says. The statue of Macdonald, representing the colonial establishment of Canada, was experienced by Dick and her elders as a daily violent reminder of their place in the colonial system.

When she heard the statue was gone, she immediately thought of her daughter and her three-year-old granddaughter. “I felt joy,” says Dick. “Now my grandkids, when they become leaders of our people, won’t have that over them. They can officially walk in as equal. I couldn’t do that. My parents couldn’t do that. My elders couldn’t do that.”

Dick feels hopeful about the world her granddaughter will grow up in. Not just because one statue was removed, but due to the entire process of reconciliation happening within the City of Victoria.

“I see people taking statues down all over Canada and the U.S., but not understanding our point of view,” says Dick. Victoria, in contrast, is taking measures to break down the centuries-old barriers between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in the area, Dick feels. Victoria is providing reconciliation training for all city staff and has hosted a conversation series organized by the City Family to educate the public about the history of Victoria and the Lekwungen People, the principles of UNDRIP and the impacts of colonization on Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

In addition, the 2019-2022 Strategic Plan for the City of Victoria outlines 17 specific actions to be taken for “Reconciliation and Indigenous Relations.” The actions should create systemic change, says Mayor Helps, and ensure reconciliation becomes “embedded in the practice of the city” through a diverse range of measures, from increased visibility of Indigenous Peoples and cultures throughout the city to more difficult conversations about land sovereignty.

Another goal? To make the City Family a “core program” for Victoria.“No one can create a program that is untouchable, but we can make it as difficult as possible to break it down,” says Alto. “That’s the goal.”

Alto keeps alive in her memory a story told to her by an Indigenous Elder at an early meeting about how to advance reconciliation in Victoria.

“This program is like all things,” the Elder said, “a journey that starts with a canoe. And you get in a canoe and set off on the river. You know that eventually all rivers lead to the ocean, but they all take different routes.

“Once in a while you’ll get stuck in an eddy, or hit a branch, and it may seem to you that it slows or impedes your progress. But at that moment something else will happen which is important for you to see and learn.”

“Eventually, you will reach the ocean. It may take you a very long time, or a short time.” Most importantly, says Alto, “reaching the ocean is not reconciliation. Being on the river is reconciliation.”

Bill Stewart, for his part, is pleased to see a new bend in that river. “I grew up with the idea of Canada the Good, and I shared that dream,” he says. Taking satisfaction in the demise of a monument to John A. Macdonald is “not about trying to tear it down,” he says. It’s about “trying to move from the ideal of Canada the Good to the reality.”

Cole Pauls is a Tahltan comic artist, illustrator and printmaker hailing from Haines Junction (Yukon Territory) with a BFA in illustration from Emily Carr University. Residing in Vancouver, Pauls focuses on his two comic series, Pizza Punks: a self contained comic strip about punks eating pizza, and Dakwäkãda Warriors. In 2017, Pauls won Broken Pencil Magazine’s Best Comic and Best Zine of the Year Award for Dakwäkãda Warriors II. In 2020, Dakwäkãda Warriors won Best Work in an Indigenous Language from the Indigenous Voices Awards and was nominated for the Doug Wright Award categories, The Egghead & The Nipper.