Victoria was sitting on the hood of a parked car looking down at the number she had been given by a staffer at the Planned Parenthood clinic where she’d had her abortion a few days earlier. She felt sure she had made the right decision by terminating the pregnancy. She was just 20 years old, holding down three jobs and on the cusp of finishing college.

Still, she couldn’t shake the feeling that she had let her Catholic, pro-life family down. “It felt to me to be very shameful,” she says. She called the number and, before she knew it, she was telling the woman, a peer counselor for an organization called Exhale, about a recurring dream she had been having. “I would be speaking to my sister, but she would not turn to face me when we talked — no matter how I walked around her or asked her to.”

The counselor listened intently and helped Victoria — who asked that her last name not be used to protect her family’s privacy — to reflect on her experience. “It was really good for me to put everything on pause and be like, ‘Oh, this is actually a little bit confusing what I’m feeling,” she says. She called the talk line a few more times and each conversation was the same. “Nobody said anything except things like, ‘You deserve to heal’ or ‘You deserve peace.’”

At a time when attitudes toward abortion are deeply divided along ideological lines, organizations like Exhale — whose clients include both feminists from California and churchgoers from the Bible Belt — are a rarity.

Most abortion counseling organizations are either pro-life or pro-choice. Pro-life organizations believe abortion is morally wrong and often see counseling as an opportunity to “save” women who have committed what they view as a grave sin, sometimes through shame or coercion. Pro-choice organizations seek to normalize abortion and often downplay or dismiss women’s feelings of loss, confusion, or regret after having one.

“There’s really no space to wrestle with it because we’re just screaming over one another,” says Susan Chorley, a Baptist minister and president and co-founder of Exhale. Chorley got pregnant for the second time when her son was two and her marriage was on the rocks. The thought of having another child overwhelmed her and she chose to have an abortion. After the procedure, she didn’t dare talk about it with people at her church for fear of being ostracized. At the same time, pro-choice groups didn’t acknowledge the full range of emotions she felt about her abortion, which included intense sadness.

Both sides made her feel judged. “It was like, ‘Just do it and who cares’ or, ‘If you do that, you’re forever damned,’” Chorley says. “It’s so much more complex.”

The isolation she felt led Chorley, who is still a minister, to co-found Exhale, a non-profit that helps people process their experiences around abortion without any preconceived notions about what that should look like. “It doesn’t matter where you are on the political spectrum,” says Chorley. “Your experience, your questioning of what it means, your questioning of who you are as a result of it — all those things are in that conversation. And there’s no space to have that conversation if we’re just talking about whether it’s right or wrong.”

Founded in 2000, Exhale is staffed by 40 volunteers from across the country trained to act as non-partisan, non-judgmental sounding boards for women (and sometimes men) who have experienced abortion. It has staunchly resisted pressure from donors and others to plant its flag in either the pro-life or pro-choice camps. Instead, it has tried to carve out a space, which it calls “pro-voice,” in the sparsely occupied territory between the two extremes.

“I think that some of the division and isolation that we’re experiencing in this country has been because there haven’t been enough opportunities for people across those quote-unquote divides to find one another, to know one another, to listen to one another,” says Chorley. “Ultimately, that’s what we want to create in this space.”

The organization recently hosted a series of virtual healing circles for people who have had an abortion and have also been victims of violence (many women make the decision to abort because they have been victims of sexual assault or domestic abuse). The circles consisted of three activities per week, including journaling, yoga and weekly group discussions, for a period of six weeks. At any time, people can connect with a counselor via the organization’s text line (this year, Exhale transitioned management of the talk line to another organization, Connect and Breathe).

Most people reach out because they have nobody else to talk to or are afraid of what people will say. “You need to sit there and hold a safe space for them so they can talk about their feelings,” says Jenna Sprague, a peer counselor for Exhale who also sits on the organization’s board. “It’s giving people the chance to actually use their voice.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

Clients set the agenda for the conversation with peer counselors following their cues, right down to what language they use. “If they say baby, we reflect that back and talk about their baby,” Sprague says.

Text line counselors attend eight hours of virtual training over two weekends, where they role play situations they may encounter with clients — a college student grappling with the decision, a father wanting to support his teenage daughter, a grandmother coming to terms with an abortion she had years ago.

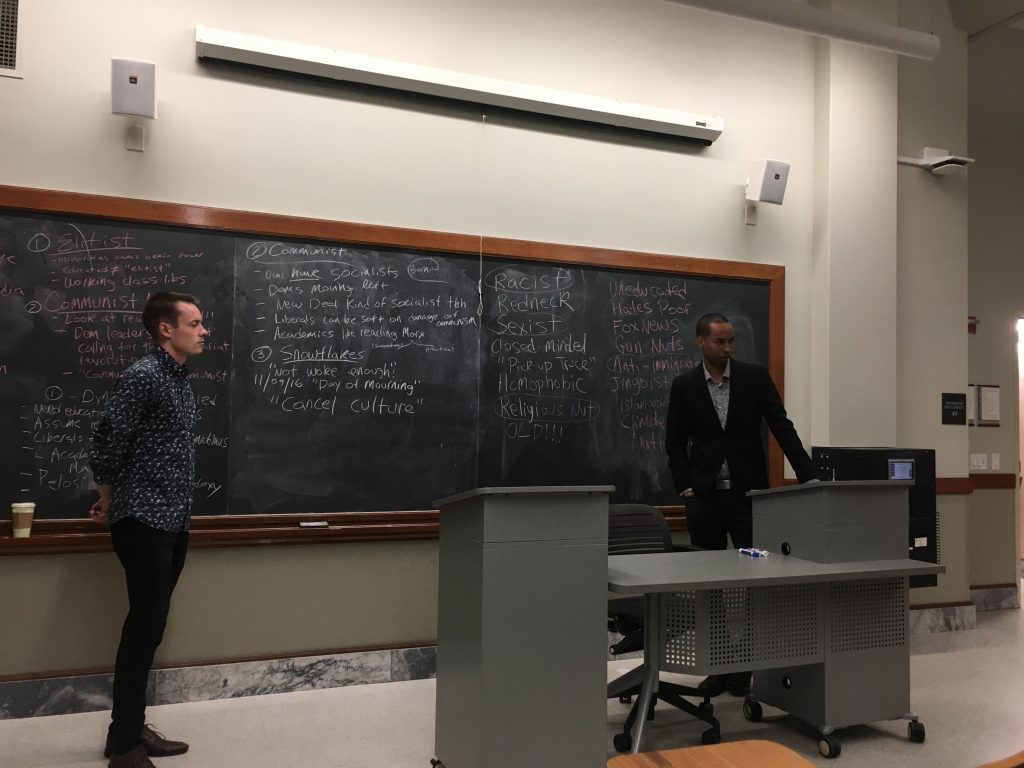

One of the goals of the training is to unpack participants’ assumptions about abortion.

When Sprague trained with Exhale in 2016, the organization was doing in-person sessions at their now shuttered office in Oakland, California. In one session, the trainer asked participants questions like, “Do you believe abortion is a form of killing?” and “Is abortion a form of birth control?” “We had a ‘Yes’ section and a ‘No’ section and you could stand anywhere along that wall,” Sprague recalls. After hearing why other participants felt the way they did, several people shifted from their original positions along the wall.

For Sprague, this simple exercise was revealing. “It was a great way to tangibly see that it’s not a black-and-white issue. There are different layers to this.”

That approach reflects a level of empathy and complexity that is arguably missing from the abortion debate — but it hasn’t been an easy sell.

“The middle ground isn’t flashy,” says Sprague. “Being on the extremes…it brings in more money, it brings in more followers, it generates more conversation.” In recent years, the organization has struggled to attract donors and funding constraints have forced it to scale down, including divesting the talk line.

Despite these challenges, Chorley isn’t budging. “I’ve given up on trying to fight to belong,” she says. “I am committed to creating space for people who want a nuanced conversation.”

A version of story originally appeared in the book “

A version of story originally appeared in the book “